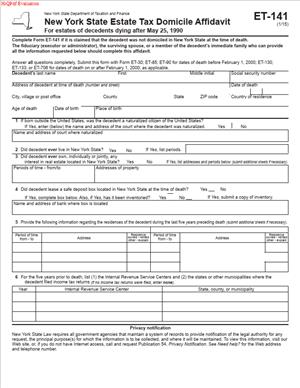

ET-141 – New York State Estate Tax Domicile Affidavit

Fill out nowJurisdiction: Country: USA | Province or State: New York

What is an ET-141 – New York State Estate Tax Domicile Affidavit?

The ET-141 is a sworn statement about a decedent’s domicile. You use it to show where the person was legally domiciled at death. Domicile means the one true, fixed home a person intends to return to. It is different from a simple residence or where someone spends time.

New York uses this affidavit in estate tax matters. The state needs to know if the decedent was a New York domiciliary. If the decedent was domiciled in New York, the estate may face New York estate tax on worldwide assets. If the decedent was not domiciled in New York, tax may apply only to certain New York assets. That includes New York real estate and some tangible property located in New York.

This form captures facts that show domicile. It asks about homes, time spent, family ties, business ties, and civic connections. It also covers voter registration, driver’s licenses, vehicle registrations, and tax filing history. The affidavit includes a sworn statement by someone with direct knowledge. It must be signed and notarized.

You typically see this form when there is a question about domicile. The estate may claim that the decedent moved out of New York. Or the state may question a recent relocation to New York. The affidavit helps resolve the dispute.

Who typically uses this form?

Executors often prepare and sign it. So do administrators, personal representatives, and trustees if the return is filed by a trust. Attorneys, accountants, or family members with direct knowledge may also act as affiants. Sometimes multiple affiants provide separate affidavits. Each affiant must have personal knowledge of key facts.

Why would you need this form?

You use it to support the estate’s position on domicile. The form helps the state decide if the New York estate tax applies and to what assets. It reduces uncertainty and can help avoid an audit or speed one up. It also provides a structured way to present consistent evidence.

Typical usage scenarios include a “snowbird” with homes in New York and Florida. It also includes a person who sold a New York home and moved to another state. It includes a person who returned to New York late in life for medical care. It includes a person who kept a New York apartment but claimed a new domicile elsewhere. It also includes nonresidents who owned New York real estate at death. In all cases, the form organizes the facts and supports the estate’s position.

When Would You Use an ET-141 – New York State Estate Tax Domicile Affidavit?

You use this affidavit when the decedent’s domicile is not clear. If the estate files a New York estate tax return and domicile is at issue, include the form. If New York questions your domicile claim during review, submit it then. If another state also claims domicile, prepare the affidavit to bolster your New York position. You also use it when a nonresident estate holds New York property. It helps establish that New York should not tax non–New York assets.

Consider a snowbird who splits time between New York and Florida. They kept a Florida driver’s license and a homestead exemption. They also maintained a New York condo and voted in New York. The affidavit shows which state was the true home. It could make or break the estate’s tax exposure.

Consider a retiree who moved to North Carolina. They sold the New York house two years before their death. They updated licenses, doctors, clubs, and tax returns to North Carolina. The affidavit will collect those facts in one place. It will then anchor the estate’s nonresident filing position.

Consider a business owner who still had a New York office. They relocated their family to New Jersey and joined local organizations. Their children attended school in New Jersey. The affidavit weighs those facts against New York connections. It helps the state determine the person’s true intent.

Executors are the most common users. Administrators, trustees, and attorneys also use it. Accountants often help gather records and organize exhibits. Family members or close friends with direct knowledge can sign as affiants, too. Choose affiants who can speak to day-to-day facts and long-term intent. The more specific and documented the facts, the stronger your position.

You should also use the affidavit if the decedent recently changed addresses. Moves within the last few years draw extra scrutiny. Use the affidavit to show timely updates to documents and registrations. Support it with buyer and seller closing files, leases, and utility bills. Include evidence of new community ties.

In audits, the auditor may ask for this form. Provide it promptly with attachments. Consistency across the return, affidavit, and exhibits is critical. If your facts conflict, expect questions and possible adjustments.

Legal Characteristics of the ET-141 – New York State Estate Tax Domicile Affidavit

The ET-141 is a sworn affidavit. It is legally binding because you sign under penalties of perjury. A notary public must witness your signature. This ensures you understand the oath and the consequences of false statements. The state relies on the affidavit to make tax determinations. False statements may trigger penalties, interest, or criminal exposure.

Enforceability rests on several elements. First, the oath and notarization establish the weight of your statements. Second, the form requests objective facts and supporting documents. Third, the estate tax authorities use the information in examination and assessment. They may compare the affidavit with other filings. That includes income tax returns, property records, and license databases. If there are conflicts, the state can propose changes. The state can also request more evidence or testimony.

The affidavit does not “decide” domicile by itself. It is part of the factual record. Domicile is a legal conclusion based on intent and conduct. No single factor controls the outcome. Actions speak louder than stated intent. The state looks for a pattern over time that aligns with the claimed domicile. Your affidavit should reflect that pattern with concrete facts.

As a legal matter, each estate bears the burden to prove its position. If you claim nonresident status, you must substantiate it. The affidavit helps you meet that burden. Detailed attachments, calendars, and copies carry significant weight. Affiants should stick to facts within personal knowledge. If you do not know something, say so. Do not speculate.

There are also privacy and accuracy considerations. Include only relevant facts and documents. Redact sensitive numbers except where required. Keep a copy of the signed and notarized affidavit. Keep your exhibits organized and labeled. You may need them again during review or appeal.

Finally, remember that domicile is singular. A person has only one domicile at a time. You cannot be domiciled in two states. The affidavit should tell a clear, consistent story. Show how the decedent chose one home and left the other. Timelines and dated records are essential to that story.

How to Fill Out an ET-141 – New York State Estate Tax Domicile Affidavit

Follow these steps. Gather documents before you start. You will save time and avoid errors.

1) Confirm the filing need and role.

- Decide why you need the affidavit. Is the domicile disputed or unclear?

- Confirm who will sign. The executor is ideal. A person with first-hand knowledge also works.

- If more than one person has key facts, prepare multiple affidavits.

2) Collect core documents.

- Letters testamentary or administration.

- The death certificate.

- The decedent’s last two to three years of income tax returns.

- Driver’s licenses and vehicle registrations for the last five years.

- Voter registration records and voting history, if available.

- Deeds, leases, and closing statements for all homes.

- Utility bills and insurance statements for each property.

- Travel calendars and flight records.

- Club, church, and organization memberships.

- Banking and brokerage statements with mailing addresses.

- Homestead exemption or STAR records, if any.

- Professional licenses and business filings.

- Medical provider and insurance correspondence showing address changes.

- Cemetery plot purchase records and funeral arrangements.

3) Complete decedent identification.

- Enter the full legal name and Social Security number.

- Provide date of death and date of birth.

- List the address at death as shown in official records.

- If the address at death differs from the claimed domicile, be ready to explain why.

4) Identify the affiant.

- Provide your full name, address, and phone number.

- State your relationship to the decedent. For example, the executor or the spouse.

- Explain your basis of knowledge. For example, lived together and handled mail.

- If you are the fiduciary, note your appointment and attach proof.

5) State the claimed domicile.

- Identify the state and exact address of the claimed domicile.

- Provide the date the decedent established that domicile.

- Explain when and how the decedent abandoned any prior domicile.

- Keep this statement concise and fact-driven.

6) Describe each residence.

- List every residence the decedent used in the last five years.

- For each, include the address, ownership or lease status, and occupancy dates.

- Note which residence was used as the principal home and why.

- Include copies of deeds, leases, or closing statements.

7) Show the time spent by location.

- Provide the number of days spent in New York in the last two years.

- Provide the number of days spent in the claimed domicile state.

- Include a day-by-day calendar if you have one.

- Use travel records, utility usage, and device logs to corroborate.

- Explain seasonal patterns, like winters in Florida.

8) Family and personal ties.

- State where the spouse or partner lived, if any.

- State where minor children lived and attended school.

- List primary doctors, dentists, and other providers by state.

- Describe religious, social, and community memberships by state.

- Include copies of membership cards or letters.

9) Civic registrations and licenses.

- Provide driver’s license numbers and issuing states with issue dates.

- Provide vehicle registration states and plate numbers.

- State voter registration location and last votes cast, if known.

- List jury service summons or responses by state.

- Include professional licenses and their registered addresses.

10) Employment and business ties.

- Identify the principal place of employment or business.

- State the location of any office and the nature of duties.

- Provide ownership interests in entities and where they operate.

- Include lease copies for offices and business registrations.

- Explain any New York presence and its significance.

11) Financial and administrative ties.

- List banks and brokerages with the address of record.

- Note safe deposit boxes and their locations.

- Provide the mailing address used for financial accounts.

- Include account statements showing address changes.

- Identify the address on insurance policies and credit card bills.

12) Property and tangible items.

- Explain where household goods and valuables were kept.

- Note the location of items of sentimental value.

- Identify the location of pets, vehicles, and boats.

- Describe where the main art, photos, or heirlooms were displayed.

- Include property insurance schedules if helpful.

13) Tax filing history.

- State whether the decedent filed New York resident or nonresident returns.

- Identify other states where returns were filed and on what basis.

- Provide copies of first pages and address pages.

- Explain any change in filing status and when it occurred.

14) Homestead and exemptions.

- Identify any homestead exemptions claimed in other states.

- Provide the address and dates for those exemptions.

- If a New York STAR benefit was claimed, explain the history and end date.

- Attach proof of exemption filings or terminations.

15) Burial and estate planning indicia.

- Note the location of the cemetery plot and burial.

- Cite the address in the will and codicils, if any.

- Identify the state law governing any trusts, if stated.

- Attach the will’s introductory page and signature page if relevant.

16) Prepare the narrative explanation.

- Draft a short summary of the domicile story.

- Keep it chronological and focused on actions, not just intent.

- Point to key documents by label, like Exhibit A or B.

- Avoid broad claims without proof.

17) Attach exhibits and label them.

- Create a simple index of exhibits.

- Label each document with a clear exhibit number.

- Ensure dates are legible and consistent.

- Redact sensitive data except where required.

18) Review for consistency.

- Check that addresses and dates match across all sections.

- Confirm the number of days in New York tied to the calendar.

- Align your statements with returns and licenses.

- Correct any typos or mismatches.

19) Sign and notarize.

- Read the perjury statement carefully.

- Sign in the presence of a notary public.

- The notary will complete the acknowledgment.

- Date the affidavit on the signing day.

20) File and retain copies.

- Include the affidavit with the estate tax filing if domicile is at issue.

- If an auditor requested it, submit directly to that auditor.

- Keep a complete copy of the estate records.

- Store the original or a certified copy as instructed.

Common mistakes to avoid:

- Vague statements like “always intended to return.” Replace with actions and dates.

- Ignoring New York ties. Address them and explain their limited weight.

- Missing calendars. Reconstruct travel from emails, tickets, and bills if needed.

- Incomplete address updates. Show when and how addresses changed.

- Unlabeled exhibits. Use a clear index so reviewers can follow.

Practical examples:

- A decedent kept a New York apartment for occasional visits. They moved their spouse, doctors, clubs, and licenses to another state. They claimed that the state’s homestead law and voted there. The affidavit shows a completed move. New York ties are secondary and infrequent.

- A decedent worked in New York three days a week. Their family and home were in Connecticut. Their license, voting, and doctors were in Connecticut. The affidavit supports a non–New York domicile despite work in New York.

- A decedent entered a New York nursing facility late in life. Their long-time home, license, and community remained in another state. The affidavit shows a temporary presence in New York for care, not a domicile change.

Final tips:

- Start early. It takes time to gather records.

- Be precise. Dates and addresses matter.

- Be honest. If there are bad facts, explain them.

- Be complete. Attach documents that back your key points.

- Be consistent. Domicile cases turn on a coherent story.

With a thorough affidavit and solid evidence, you can present a clear domicile position. That clarity helps the state make a fair assessment. It also helps you avoid delays, penalties, and extended audits.

Legal Terms You Might Encounter

- Domicile means the place you consider your true, fixed, permanent home. It’s where you intend to return after any time away. The ET-141 focuses on facts that show the decedent’s domicile at death. You use it to explain why New York was, or was not, the decedent’s permanent home.

- Residence is where someone lives at a given time. You can have many residences, but only one domicile. On ET-141, you distinguish temporary residences from the decedent’s permanent home. The distinction supports the estate’s tax position.

- Decedent means the person who died. The form asks for the decedent’s facts, not yours. You provide their addresses, habits, and ties to places to show where they truly lived.

- Executor or Administrator is the person managing the estate. If there is a will, the executor serves. If not, an administrator is appointed. The executor or administrator often signs the ET-141. The form expects that the signer to have personal knowledge of the decedent’s life and property.

- Affiant is the person who signs an affidavit under oath. On ET-141, the affiant is usually the executor or administrator. If you sign, you swear the facts are true to the best of your knowledge.

- Affidavit is a written statement made under oath and notarized. ET-141 is an affidavit. That means your statements carry weight and must be accurate. False statements can lead to penalties.

- Situs refers to the legal location of property. For estate tax, it matters where real estate and tangible items are located. ET-141 asks about property locations to help determine New York’s reach over the estate.

- Nonresident estate is an estate of a decedent not domiciled in New York at death. ET-141 helps you prove that status. If the decedent was a nonresident, New York may only tax certain New York–located assets.

- New York estate tax return is the state filing that reports the estate for tax. If a return is required, you often attach ET-141. The affidavit supports the residency section of the return.

- Notarization is the formal witnessing of your signature by a notary. Because ET-141 is an affidavit, you sign it before a notary. The notary confirms your identity and that you signed under oath.

FAQs

Do you need to file ET-141 if the decedent was clearly a New York resident?

You typically file ET-141 when the domicile is unclear or disputed. You also use it when you claim the decedent was not domiciled in New York. If the decedent was obviously a New York domiciliary, the estate may not need the affidavit. That said, attaching a complete ET-141 can head off questions and reduce delays. Match the affidavit to the facts and the estate’s tax filing.

Do you file ET-141 without filing a New York estate tax return?

You generally submit ET-141 with the estate tax return when domicile matters. If a return is not required, you may not need to file the affidavit. However, the tax department can ask for ET-141 during a review or inquiry. Keep it ready with the estate file in case you need to respond.

Do you need to get ET-141 notarized?

Yes. It is an affidavit and must be signed under oath before a notary. Bring valid ID to the signing. Sign in the notary’s presence. Make sure the notary completes their section in full. If you mail the form, use an original notarized signature unless instructions allow otherwise.

Do you need to include attachments with ET-141?

You should include documents that support key statements. Examples include the decedent’s driver’s license, voter registration, state income tax returns, property deeds, and utility bills. Add travel logs or calendars if day count matters. Label exhibits and tie them to specific answers on the form. Clear attachments can prevent follow-up requests.

Do you need to count the decedent’s days in and out of New York?

Often, yes. Day count can be a strong indicator of where the decedent actually lived. Provide a reasonable, documented estimate if exact counts are not available. Use calendars, flight records, toll statements, and phone records to corroborate. Explain your method so the reviewer can follow it.

Do you list all addresses or only the last one?

List each relevant address during the period the form covers. Include the primary home, any vacation homes, and any temporary stays. State which address you believe was the domicile and why. Consistency with other documents strengthens your position.

Do you need multiple affidavits if there are co-executors?

Usually, one well-informed affiant is sufficient. If knowledge is split among co-executors, each can submit an affidavit. If someone other than the executor has key facts, they can also sign an affidavit. The goal is to complete, well-supported facts from someone with personal knowledge.

Do you amend ET-141 if you later discover an error?

Yes. Prepare a corrected affidavit with the new facts. Identify what changed and why. Attach updated supporting documents. Submit the corrected version with a cover explanation to the same place you sent the original filing. Keep both versions in the estate file.

Checklist: Before, During, and After the ET-141 – New York State Estate Tax Domicile Affidavit

Before signing: Information and documents you need

- Decedent’s full legal name, Social Security number, and date of death.

- All home addresses for the last several years, with move-in and move-out dates.

- Copies of driver’s licenses and state IDs, with issue and renewal data.

- Voter registration confirmations and voting histories.

- State and local income tax returns for recent years.

- Property deeds, mortgage statements, and property tax bills for all homes.

- Lease agreements, homestead exemptions, or primary residence filings.

- Utility bills and service start dates for each residence.

- Bank and brokerage statements showing branch or safe deposit box locations.

- Business ownership records and principal place of business.

- Vehicle registrations and titles showing garaging locations.

- Memberships and affiliations (clubs, religious institutions, professional groups).

- Medical providers’ locations and primary care records addresses.

- Burial or interment location details.

- Travel records and calendars showing time spent in and out of New York.

- Insurance policies with correspondence addresses and policy situs notes.

- The will and any letter of intent that mentions the decedent’s home.

- Prior correspondence with tax authorities about residency or domicile.

- Contact info for people who can corroborate facts, if needed.

During signing: Sections to verify carefully

- Names and dates. Confirm the decedent’s name, date of death, and your role.

- Address history. Ensure dates do not overlap and match other filings.

- Day counts. Check your math and your date ranges. Explain your method.

- Property details. Confirm locations and ownership type for each property.

- Government ties. Align driver’s license, voter registration, and tax filings.

- Business connections. Identify the business location and the decedent’s active involvement.

- Family ties. Note spouse and dependents’ residences during the period.

- Attachments. Cross-reference each attachment to the relevant statement.

- Consistency. Match facts to the estate tax return and probate filings.

- Notary block. Sign in front of the notary. Verify that the notary completes their section.

- Capacity. Sign with your legal title (Executor, Administrator, or Affiant).

After signing: Filing, notifying, and storing

- Attach. Include the notarized ET-141 with the estate tax return if filing one.

- Submit. Send the package as directed by the return instructions. Use traceable mail.

- Confirm. Keep proof of delivery and a filing cover sheet in the estate file.

- Notify. Inform co-fiduciaries that the affidavit was filed and provide copies.

- Track. Calendar response deadlines for any notices or information requests.

- Amend. File a corrected affidavit if you uncover new facts or documents.

- Coordinate. Align the affidavit with applications for any tax releases affecting property.

- Store. Keep the signed original and attachments in the estate’s permanent records.

- Retain. Preserve records for the full retention period you use for estate tax matters.

Common Mistakes to Avoid ET-141 – New York State Estate Tax Domicile Affidavit

- Mixing up residence and domicile. Listing where the decedent stayed without addressing intent can mislead. Consequence: reviewers may treat a temporary stay as the permanent home. Don’t forget to explain why one location was the decedent’s true home.

- Leaving gaps in the address timeline. Missing months or overlapping dates invite questions. Consequence: processing delays and document requests. Don’t forget to line up dates with leases, utility starts, and moves.

- Ignoring New York situs property. Overlooking a New York condo, boat, or safe deposit box weakens the filing. Consequence: unexpected tax exposure, penalties, or amended filings. Don’t forget to list all real and tangible property and where it sits.

- Missing notarization or incomplete notary details. An unsigned or improperly notarized affidavit is invalid. Consequence: rejection of the filing and new notarization. Don’t forget to sign in front of a notary and check their seal and date.

- Using broad claims without backup. Vague statements like “lived mostly in Florida” won’t carry weight. Consequence: audit risk and requests for proof. Don’t forget to attach documents that support each key fact.

What to Do After Filling Out the Form ET-141 – New York State Estate Tax Domicile Affidavit

- Attach the affidavit to the estate tax return if you are filing one. Place it immediately behind the residency section or as directed by the return instructions. Include your labeled attachments.

- Send the full package using a trackable method. Keep the mailing receipt and a copy of everything sent. If you e-file through an authorized process, follow the upload steps and save the confirmation.

- Coordinate payment if tax is due. The domicile determination can change what is taxable in New York. Confirm that the tax calculation matches the domicile position in ET-141.

- Prepare for questions. Build a response folder with extra copies of IDs, returns, bills, and travel records. If a notice arrives, reply on time and reference the sections of ET-141 that address the issue.

- Update if facts change. If you find a new document or discover an error, prepare a corrected affidavit. Explain the change and provide the new attachments. Send it to the same place you filed the return or as instructed in any notice.

- Align other estate tasks. Domicile can affect probate venue, tax clearances, and property transfers. Make sure your filings, deeds, and beneficiary communications match the position in ET-141.

- Request confirmations, if available. Keep any acknowledgement or closing correspondence with the estate file. Note the date the review appears complete for your records.

- Maintain records. Keep the original signed affidavit, attachments, and mailing proof in the estate file. Retain records for the full period you use for tax documents. A longer retention window reduces risk if questions arise later.

- Communicate with beneficiaries. Let them know the filing status and any impact on timing. Clear updates reduce confusion and help you manage expectations.

- Follow up on liens affecting real property. If a tax release is required for a sale or transfer, coordinate early. Ensure the domicile position and supporting documents align with any release application.

- Plan for final steps. Once tax matters are resolved, close out the estate’s tax file, store all documents safely. Note what you would need if an agency reopens the file later.

Disclaimer: This guide is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as legal advice. You should consult a legal professional.