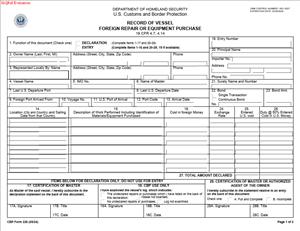

CBP Form 226 – Record of Vessel Foreign Repair or Equipment Purchase

Fill out nowJurisdiction: Country: USA | Province or State: Federal

What is a CBP Form 226 – Record of Vessel Foreign Repair or Equipment Purchase?

CBP Form 226 is the official record you file with U.S. Customs and Border Protection when a U.S.-documented vessel has repairs or equipment purchases done outside the United States. It is how you disclose what work was done abroad, what equipment was bought, where, and at what cost. Customs uses this form and your attached invoices to determine any duty owed under federal law governing foreign repairs and equipment for U.S. vessels. The form also creates the record you need if you will request relief from duty for certain items.

In simple terms, this is your compliance report for foreign yard periods, voyage repairs, and overseas equipment purchases. It covers work performed outside U.S. customs territory, including shipyard jobs, vendor service calls, and equipment sourced or installed abroad. You complete it at your first U.S. port of arrival after the foreign work or purchase.

Who Typically Uses This Form?

Typical filers are the vessel owner, operator, master, or an authorized vessel agent. Many companies also use a licensed customs broker to prepare and submit the filing. The form applies to U.S.-documented commercial vessels that trade internationally or otherwise call foreign ports. That includes container ships, tankers, bulkers, offshore service vessels, tugs, barges with documentation, dredges, and many fishing vessels. If your vessel is documented under U.S. law and you had foreign repairs or bought equipment abroad, you are in scope.

Why would you need this form?

You file CBP Form 226 to meet a federal reporting duty tied to vessel repairs and equipment purchases abroad. Customs uses your filing to:

- Calculate any duty due on foreign repairs, equipment, and parts.

- Decide which items qualify for relief from duty.

- Review whether charges were truly repairs, modifications, or non-dutiable services.

- Verify the accuracy of your declarations and invoices.

Filing on time protects you from penalties and delays. It also allows you to present your best case for non-dutiable items and any relief claims. You want the record to be complete, itemized, and supported by proper documents. That starts with this form.

Typical usage scenarios

You sail a U.S.-documented tanker to a foreign yard for routine drydocking. The yard completes steel renewals, coating, and machinery overhauls. You also install a new ballast water management system. You must file CBP Form 226 at your first U.S. port. You will itemize each invoice line. You will distinguish repairs from permanent modifications and provide drawings and workpacks that show the modification scope.

You operate a U.S.-flag container ship that suffers a pump failure in Singapore. A local contractor repairs the pump. You also buy a spare pump on the spot. You report both the repair service and the purchased spare on CBP Form 226 when you arrive in a U.S. port. If the spare pump was manufactured in the United States and exported previously, you may claim relief for that item with proof.

You run an offshore supply vessel. A technician boards in Mexico to install a new satellite communications unit. You buy the unit abroad. You report the equipment purchase and the installation charges on CBP Form 226. You support your position that the installation is a modification rather than a repair, if applicable.

You manage a dredge that suffers storm damage off a foreign coast. Emergency repairs abroad are necessary to ensure seaworthiness. You disclose the repairs on CBP Form 226 and submit a casualty relief claim with logs, surveys, and evidence of the emergency.

When Would You Use a CBP Form 226 – Record of Vessel Foreign Repair or Equipment Purchase?

You use the form after a U.S.-documented vessel receives any repair work, maintenance services that restore condition, or equipment purchases outside the United States, then returns to a U.S. port. You file it at the first U.S. port of arrival for that vessel after the foreign work. You include all foreign ports where work occurred and all related vendors. If several voyages occur with multiple foreign calls before returning to the U.S., you capture the full period since the last U.S. arrival.

Typical users are vessel owners and operators in blue water trade, offshore energy support, dredging, towing, and fishing. Masters and port captains often coordinate the documents. Port agents or customs brokers usually handle the submission with CBP on arrival. You should also use the form when warranty work occurs abroad. Warranty status does not remove the reporting duty. You still report the work and show who paid.

You should file even if you believe all items are non-dutiable. Filing preserves your position and starts CBP’s review. Examples include new system installations that you classify as modifications, or parts you claim as U.S.-manufactured goods installed abroad. You will provide proof and request relief or non-dutiable treatment. The form is the entry point for those determinations.

You should also file when the vessel remains outside the United States for a yard period and returns with a large set of invoices. In that case, plan early. Ask the shipyard and vendors to split invoices between repairs and modifications. Ask for itemized labor and material line items. Make sure you can tie each invoice to a specific location and date. Detailed invoices make the review faster and reduce disputes.

Legal Characteristics of the CBP Form 226 – Record of Vessel Foreign Repair or Equipment Purchase

CBP Form 226 is an official customs filing. It is legally required for U.S.-documented vessels that had foreign repairs or equipment purchases. The form is a sworn declaration. You certify that the information and documents are true and complete. That certification carries legal consequences. False statements can trigger civil penalties and other enforcement action. Failure to file can lead to duty assessments, penalties, and delays in clearance.

The form is enforceable because federal law imposes duty on the cost of foreign repairs and equipment for covered vessels. Customs administers that law and reviews your filing. Customs can demand additional records, inspect the vessel, and audit your books. You must keep the underlying records for the required retention period. You also post a bond or make a duty deposit when you file. Customs liquidates the entry after review and issues a final duty decision. If you disagree, you can pursue administrative remedies through the standard customs processes.

Legal considerations focus on classification and proof. Customs distinguishes between dutiable “repairs” that restore condition and generally non-dutiable “modifications” that permanently improve or change the vessel’s capability. Inspections may be non-dutiable when not tied to repairs, but charges that facilitate repairs usually become dutiable. Cleaning, testing, and transport may be dutiable when related to repairs. You must segregate each charge on invoices to show what is dutiable and what is not. You must also prove any claim that parts were manufactured in the United States, or that relief applies due to casualty or other statutory grounds.

Currency conversion, exchange rates, and the timing of costs also matter. Customs will require conversion of foreign currency amounts into U.S. dollars using the officially recognized rate for the relevant date. You must apply a consistent method across all invoices. You should be prepared to support the rate used with your filing record.

How to Fill Out a CBP Form 226 – Record of Vessel Foreign Repair or Equipment Purchase

Approach the form as the cover sheet for a well-documented package. Your goal is to present a clean itemization of foreign work and purchases, supported by invoices and proof. Follow these steps.

Step 1: Gather the right documents

Collect every foreign invoice, work order, and credit note since the vessel last departed the United States. Get detailed invoices that separate labor, materials, and other charges. Ask vendors to describe each task and identify the location, dates, and equipment. If you installed a new system, obtain drawings, class approvals, and installation workpacks. If you will claim that a part is U.S.-manufactured, secure manufacturer certificates, purchase orders, and export records. If you will claim casualty relief, gather logs, survey reports, photos, and repair authorizations that show the emergency. Translate foreign-language invoices into English. Use clear, consistent invoice numbers. Confirm payment dates and currencies.

Step 2: Record vessel and voyage information

Complete the header with vessel details. Enter the vessel name, U.S. official number, and IMO number. Provide the call sign if requested. Identify the owner and operator with addresses and contact details. List the U.S. port of arrival where you are filing. Enter the arrival date and time. State the last foreign port, with departure date. This ties the work to the foreign segment of the voyage. If the vessel called multiple foreign ports for work, note each port in your attachments and cross-reference them on the form.

Step 3: Identify the filer and authority to sign

State who is filing: the owner, operator, master, agent, or broker. If a broker or agent signs, include a power of attorney or agency letter. If the master signs, ensure the signature matches travel documents and that contact information is available for follow-up. Customs needs a responsible party for questions. Provide a direct phone and email.

Step 4: Itemize each foreign repair and equipment purchase

The form provides space to list work and purchases. If your list is long, attach schedules and reference them here. For each item, provide:

- Vendor name and full address.

- Location (city and country) where the work occurred or where the equipment was purchased or installed.

- Invoice number and invoice date.

- Description of the work or item. Use clear terms. For example: “Main engine cylinder head overhaul,” “Hull steel renewal, frames 140–160,” or “Install new ballast water management system.”

- Type classification: repair, modification, inspection, equipment purchase, or other. Classify conservatively and be ready to support your position.

- Dates of performance and completion.

- Currency of the invoice and the exchange rate you used.

- Cost breakdown: labor, materials, subcontractor charges, travel, freight, taxes, and other charges.

- U.S. dollar totals for each line after conversion.

Group items by vendor and by foreign port if that clarifies the record. Use consistent line numbering so CBP can trace each line to an invoice page.

Step 5: Segregate dutiable and non-dutiable charges

Customs will assess duty on dutiable repairs, repair parts, and related costs. Identify and total those charges separately. If you claim that a line is non-dutiable, say why and attach support. Examples:

- Modification: Identify new systems or structural changes that improve capability. Provide drawings, new equipment lists, and class approvals. Show that work goes beyond restoring condition.

- U.S.-manufactured parts installed abroad: Provide manufacturer certificates and purchase documents proving U.S. origin. Tie serial numbers to the invoice.

- Inspections not tied to repairs: Provide inspection reports and show that no repairs followed from that inspection.

- Casualty relief: Provide logs, surveys, and approvals that show emergency conditions and that work was necessary for safety or seaworthiness.

If invoices combine repairs and modifications, obtain a revised invoice that separates them. If not possible, prepare a detailed cost allocation with vendor confirmation. Unsupported lump sums risk being treated as fully dutiable.

Step 6: Calculate the duty base and estimated duty

Add up all dutiable charges in U.S. dollars. This sum is your duty base. The law sets the duty rate for foreign vessel repairs and equipment for covered vessels. Calculate the estimated duty on your base and enter it on the form. Be consistent with your classifications. If you are unsure about a line, do not bury it. Declare it and explain your position in a note. Your transparency builds credibility.

Step 7: Attach required schedules and evidence

Attach a schedule of invoices with index numbers, vendors, locations, currencies, and totals. Attach complete invoices, work orders, and proof of payment if available. Include translations for any non-English documents. Include drawings and technical packages for claimed modifications. Include certificates for U.S.-manufactured parts. Include casualty documentation if you seek relief. Label each attachment with the matching line number from the form. Use a clean, logical order.

Step 8: Add declarations and any relief requests

The form includes a certification that your statements are true and complete. Read it and sign. If you plan to seek relief for certain lines, note that in a remarks section and in your schedules. Some relief applications follow after the initial filing with additional forms and proofs. You still flag the claim now so CBP can hold the review open for those lines. Keep a copy of everything you submit.

Step 9: Sign and date

Have the authorized person sign and date the form. Print the signer’s name and title. Provide a direct phone number and email. If a broker signs, include the broker’s reference number and the power of attorney. If an agent signs, include the agency letter. Make sure the signature matches the authority documents.

Step 10: Submit the form and make the deposit

File the form with the CBP office at the first U.S. port of arrival. Submit your attachments at the same time or by the deadline the port provides. Be prepared to make a deposit of the estimated duty you calculated. Pay using an acceptable method at the port. Obtain a receipt and the entry number for your records. Track the filing internally so you can respond promptly to any CBP requests.

Step 11: Respond to CBP questions and keep records

CBP may ask for clarification, more documents, or revised schedules. Respond quickly and keep your positions consistent. If CBP challenges a classification, provide technical proof. If a vendor must revise an invoice, obtain it and resubmit. Keep all records for the required retention period. That includes emails with vendors, repair logs, photos, and payment records. Good records are your best defense in any review or audit.

Practical tips to avoid common problems

Ask for itemized invoices before you leave the yard. Explain to the yard that U.S. Customs will review them. Ask vendors to separate repair work from modifications and to list parts with country of origin. Obtain English descriptions.

Use clear descriptions on the form. Replace vague words like “service” with specifics such as “replace stern tube seals” or “install new VDR per spec.”

Classify prudently. Repairs restore condition and are dutiable. Modifications change capability and are often not. Support your claims with engineering documents, not just invoice labels.

Convert currency consistently. Use the accepted exchange rate method for the relevant date. Show your math for each invoice.

Do not omit small invoices. CBP reviews totals and patterns. Missing invoices raise red flags.

Do not rely on “warranty” to avoid reporting. Warranty does not remove the filing duty. If the manufacturer paid, show that clearly.

Flag emergency repairs. Provide logs and third-party reports to support casualty relief. Show that work was not deferred maintenance.

Keep a master spreadsheet. Track each invoice line, classification, currency, exchange rate, and attachment reference. This becomes your schedule and helps you answer CBP quickly.

What happens after filing

CBP reviews your form and attachments. You may receive questions about classification, scope, exchange rates, or proof of origin. CBP will then liquidate the entry and issue the final duty determination. If CBP increases the duty base or denies relief, you will see a bill for the difference. If CBP accepts your positions, your deposit becomes final duty. If you disagree with a decision, you can pursue the standard administrative review path. Keep your submission complete and consistent to reduce adjustments.

Bottom line

If your U.S.-documented vessel has foreign repairs or equipment purchases, you must file CBP Form 226 on arrival. Treat the form as your compliance summary and your best chance to make clear, supportable classifications. Itemize every line, separate repair from modification, prove any U.S. origin, and present a clean package. You will reduce duty exposure, avoid penalties, and move your vessel through the port without delays.

Legal Terms You Might Encounter

Ad valorem duty means a duty based on value. For this form, it refers to the duty assessed on the cost of foreign repairs or equipment purchases for your vessel. You calculate it from the full cost you paid abroad, not from any discounted or depreciated value. That includes labor, parts, and many related charges tied to the repair or equipment.

Dutiable costs are the amounts that may be subject to duty. For foreign repairs and equipment, this can include yard labor, parts, shop charges, testing, and some service fees. It can also include freight to the yard, drydocking, and taxes paid abroad when linked to the work. Your job on the form is to identify which costs are tied to repairs or equipment, and list them clearly.

Equipment means items that become part of the vessel’s operating gear and are not consumed during a voyage. Think of navigation electronics, winches, ladders, valves, and similar fixtures. If you bought them abroad and placed them aboard, they may be dutiable. Consumables, like fuel or food, are not equipment. This form helps you distinguish that line item by line item.

Repairs are actions that restore the vessel to working order. They fix damage, wear, or failure. Alterations or modifications change the vessel’s design or capacity, without fixing damage. The distinction matters on this form because it affects dutiability. You should label work accurately and support your label with invoices and descriptions.

Foreign port means any port outside the customs territory of the United States. Any repair work or equipment purchase that occurs there is a foreign transaction. You report those costs when the vessel returns. The form asks where and when the work occurred and what it involved.

Port of first arrival is the first U.S. port where your vessel arrives after the foreign work or purchase. This is where you must be ready to present the form and your records. Make sure the arrival details on the form match your logbook and official arrival documents.

Owner, operator, or master describes who can take responsibility for this filing. The vessel’s owner can file. So can the operator or master, or an authorized agent. The signer certifies the accuracy of the report. Make sure the signer has the authority to bind the vessel owner.

Remission or relief refers to a request to reduce or waive duty in limited situations. Typical grounds include work made necessary by casualty or stress of weather. You use the form and attachments to document why relief applies. You support it with logs, declarations, and evidence, not just invoices.

Casualty is an unexpected, sudden event that causes damage. Examples include grounding, collision, or severe weather harm. If repairs abroad were due to a casualty, you may seek relief. The form’s narratives and supporting exhibits should connect the dots from the event to the repair.

Supporting documentation is the proof behind each claimed cost and explanation. It includes invoices, work orders, receipts, warranties, logs, statements, and photos. It may also include manufacturer proof of origin for equipment. Attach clear copies and refer to them in your cost summary so CBP can follow your story.

FAQs

Do you need to file if your vessel only bought parts abroad?

Yes, if the parts qualify as equipment and were placed on board abroad. Report the cost on the form. Include any related installation labor performed abroad. If the parts are consumables, you generally do not report them here. When in doubt, review the item’s function. If it becomes part of the vessel’s gear, treat it as equipment.

Do you owe duty on labor only, parts only, or both?

You typically report the full cost of foreign repairs, which includes labor and parts. For equipment purchases installed abroad, report the price of the equipment and related charges. If you bought equipment but installed it in the United States, flag that detail. Installation location can affect how you present the cost.

Do you include taxes, fees, or drydock charges on the form?

Yes, if they are part of the repair or equipment transaction. Yard fees, testing charges, drydock time, and similar expenses often count toward the dutiable amount. Show them as separate lines with clear descriptions. If you can allocate them to non-repair work, document the basis for your allocation.

Do you file even if you plan to request remission?

Yes. File the form and disclose all foreign work and purchases. Then include your request for relief and supporting evidence. The form is your official record. The relief request explains why some or all costs should not be assessed duty.

Do you need original invoices, or are copies acceptable?

Provide legible copies that show vendor name, dates, detailed descriptions, and prices. If your invoices are in a foreign language, include a translation. If invoices are missing, gather alternative proof, such as bank records, work orders, or correspondence. The more detail you provide, the smoother the review.

Do you convert foreign currency, and how?

Yes. Convert each invoice to U.S. dollars using the appropriate rate for the transaction date. State the rate used on or with the form. Keep a record of how you determined the rate, and apply it consistently across documents from the same date range.

Do you need to separate repair and non-repair items on mixed invoices?

Yes. Ask the vendor to break out labor and parts by task. If a single charge covers both repair and non-repair work, request a revised invoice. If you must allocate a lump sum, explain your method and provide backup. Clear separation reduces questions and avoids overpayment.

Do you need to sign as the master, or can an agent sign?

An agent may sign if properly authorized by the owner or operator. Make sure the agent’s authority is in writing and ready to present. The signer certifies the accuracy of costs and statements. Choose someone who knows the facts and can respond to follow-up questions.

Checklist: Before, During, and After

Before signing: Information and documents needed

- Vessel details: name, official number, call sign, flag, owner/operator.

- Voyage details: foreign port(s) of work or purchase, dates, and the U.S. port of first arrival.

- Complete invoices: vendor names, itemized parts and labor, dates, and currency.

- Work orders and yard reports that describe tasks performed.

- Proof of equipment origin if relevant (manufacturer certificates, serial numbers, packing lists).

- Evidence for relief claims: logbook entries, incident reports, weather data, photos, crew statements.

- Payment proof: bank transfers, credit card slips, and any foreign tax receipts.

- Currency conversions for each invoice with stated exchange rates.

- Internal cost summary that categorizes repair, equipment, and other charges.

- Written authorization if an agent will sign and file for you.

During signing: Sections to verify

- Vessel identity: correct name and official number with no transposed digits.

- Arrival data: exact U.S. port, date, and time of arrival match your logs.

- Foreign work and purchase details: ports, dates, vendor names, and descriptions.

- Cost breakdown: each invoice line classified as repair, equipment, or other category used on the form.

- Currency conversion: rates applied correctly and totals reconciled to your summary.

- Relief narratives: short, factual statements tied to specific incidents and invoices.

- Attachments: complete set of invoices, translations, photos, and logs, labeled and referenced.

- Signer authority: correct title and contact details for follow-up.

- Final totals: math checked, subtotals and grand total consistent across pages.

After signing: Filing, notifying, storing

- File with the correct CBP office for the port of first arrival, following local procedures.

- Provide all supporting documents with the form in a single, organized package.

- Pay any required deposit or duty as instructed by CBP at filing.

- Get a receipt or stamped copy of what you filed. Keep a copy aboard and in your office.

- Tell your operations and finance teams. Note the potential duty impact on the voyage P&L.

- Track CBP communications and deadlines for any supplemental submissions.

- Respond promptly to any requests for additional information.

- If new invoices arrive, prepare an amendment with clear cross-references.

- Maintain your full file for your recordkeeping period. Store digital and paper copies securely.

- Schedule an internal post-voyage review to capture lessons for future filings.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Treating a modification as a repair without support

Don’t assume an upgrade is a modification. If it fixed a failure, CBP may treat it as a repair. Mislabeling can increase duty or trigger questions. Use detailed invoices and narratives to support your classification.

- Failing to separate mixed invoices

Don’t submit lump-sum invoices that blend repair, equipment, and unrelated services. CBP can assess duty on the entire amount. Ask the yard for itemization, or prepare a clear allocation with evidence.

- Leaving out incidental costs linked to the work

Don’t forget drydock, testing, inspection, shop supplies, or foreign taxes tied to the repair. If you omit them, you risk later assessments or penalties. Include and label them so your totals match reality.

- Using vague descriptions

Don’t write “general services” or “materials” without detail. That invites delays and denials of relief. Use plain descriptions that show what was done, where, and why.

- Missing the signature or filing with wrong arrival data

Don’t rush the final page. An unsigned form or wrong arrival port/date can invalidate the filing. It can also delay clearance and lead to avoidable costs.

Consequences

Errors can lead to extra duty, penalties, bond claims, or holds on clearance. Corrections take time and money. A clean, well-documented filing avoids rework and protects your schedule.

What to Do After Filling Out the Form

Submit your complete package to CBP at the port of first arrival. Include the signed form and all attachments. Present it in an order that mirrors your cost summary. Use tabs or a contents page so an officer can follow it quickly.

Confirm how CBP wants the filing. Some ports accept electronic submissions through an authorized channel. Others require in-person delivery or a specific drop-off process. Ask the port in advance so you meet expectations.

Be ready to pay any required deposit or duty at filing. Coordinate with your finance team so funds are available. Keep proof of payment with your file copy.

Expect follow-up. CBP may request more detail or clarification. Assign one point of contact to respond. When you answer, reference the specific invoice, page, and line number. Provide only what is requested, but do it quickly.

If you plan to request remission or relief, make that clear in your submission. Include your evidence with the initial filing. If you need to add more proof later, send a supplemental package. Cross-reference your original filing date and receipt number.

If you receive additional invoices after filing, prepare an amendment. Show what changed, why, and the revised totals. Include updated currency conversions and any new evidence. Mark the new pages so CBP can insert them into the original file.

When CBP issues a decision on duty or relief, review it promptly. If you agree, close out your internal case. If you disagree, consider your options for challenge within the available time window. Note any deadlines and route the decision to your leadership and counsel for review.

Update your internal records. Post the duty to the correct voyage or cost center. Record any relief granted and why. Save the final CBP decision with your file.

Conduct a brief lessons-learned session. Identify which vendors supply good itemization and which need coaching. Update your purchase and yard work instructions to reduce future filing headaches.

Keep the vessel package complete on board until your team confirms the case is closed. Store the master file in your office for your record-keeping period. Ensure backups exist in two places.

Disclaimer: This guide is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as legal advice. You should consult a legal professional.