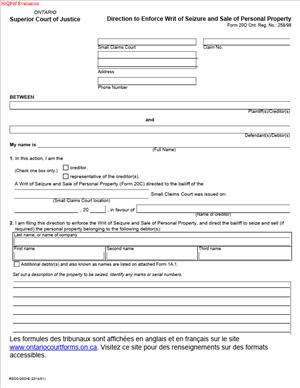

Form 20O – Direction to Enforce Writ of Seizure and Sale of Personal Property

Fill out nowJurisdiction: Country: Canada | Province or State: Ontario

What is a Form 20O – Direction to Enforce Writ of Seizure and Sale of Personal Property?

Form 20O tells the court’s enforcement office how to act on your writ. You have a Small Claims Court judgment. You also have a Writ of Seizure and Sale of Personal Property filed with an enforcement office. Form 20O gives the sheriff clear instructions to seize and sell the debtor’s personal property to pay your judgment.

You use this form after you have a judgment and a writ in place. The writ gives legal authority to enforce. The direction tells the enforcement office where to go, what to look for, and how much to collect. It also provides the debtor’s identifying details and your contact information. Without a direction, the sheriff does not know where to act.

Who typically uses this form?

Judgment creditors in Small Claims Court. That includes individuals, tradespeople, contractors, landlords, property managers, professionals, and small or mid-sized businesses. You can use it whether you are self-represented or you have a lawyer or licensed paralegal.

You would need this form if the debtor has personal property in Ontario that can be seized. Personal property includes goods like vehicles, equipment, inventory, and non-exempt tools. It does not include land. It also does not include wages or bank accounts. Use garnishment for those. If you believe the debtor owns valuable goods within a specific county, this form directs the sheriff in that county to act.

Typical usage scenarios include these. You won a judgment for unpaid renovation work. The debtor runs a landscaping business with mowers and trailers. You file a writ in the county where the equipment sits. You then complete Form 20O with the business yard’s address and equipment list. Or you are a landlord with a judgment for arrears. The former tenant runs a food truck with known storage. You direct seizure of the truck. Another example is a retailer who owes you for unpaid inventory. You know their store and stockroom location. You direct seizure of floor inventory and back stock. In each case, you tell the enforcement office what assets to target and where.

Form 20O is not a request to the court for a new order. It is a practical instruction to enforce the existing writ. It complements, rather than replaces, your writ and judgment.

When Would You Use a Form 20O – Direction to Enforce Writ of Seizure and Sale of Personal Property?

You use Form 20O when you have a valid Small Claims Court judgment and a filed writ, and you want the sheriff to seize personal property. The right time is when the debtor has known assets in a county enforcement area and has not paid. You should have specific locations and property in mind. The sheriff carries out physical seizures. Clear directions improve results.

If you are a contractor, you might direct seizure of a debtor’s skid steer at their yard. If you are a supplier, you might target inventory at a store. If you are a landlord, you might name appliances or business equipment left at a unit. If you are an individual, you might identify a vehicle in the debtor’s driveway. You can also direct seizure at multiple locations if you file the writ in each relevant enforcement office.

You would not use this form to seize land. Use a writ of seizure and sale of land for that. You would not use it to reach wages or bank accounts. Use garnishment instead. You also would not use it when assets are outside Ontario, on federal property, or in another province. The sheriff works within the county enforcement area. You may need to file and direct in each county where property sits.

Do not use it if the debtor is in bankruptcy or there is a court-ordered stay. Do not use it if the asset is clearly exempt, fully leased, or fully encumbered, unless you want the sheriff to confirm status. Exempt property is protected by law. Common examples include basic household goods and a limited value in a personal vehicle and tools of the trade. Encumbered property is subject to prior security interests. If an asset is fully financed or pledged, there may be no equity to seize.

Timing matters. If your writ is older and near expiry, renew it before directing enforcement. If the debtor has begun to move assets, act quickly. Priority usually follows the date the writ was filed with the enforcement office. Acting sooner can help preserve your place in line. If you learn of a new address or new vehicle, file a new direction with updated details.

Legal Characteristics of the Form 20O – Direction to Enforce Writ of Seizure and Sale of Personal Property

Form 20O is part of the enforcement process in Small Claims Court. It is not a judgment. It is not a new order. It is an instruction to the enforcement office to act on your writ. It is legally effective because it ties to a valid judgment and a writ filed in the enforcement office. The sheriff relies on your direction to locate and seize specific personal property.

Enforceability flows from three items. First, your judgment grants you a right to enforce. Second, the writ translates that right into authority the sheriff can use. Third, the direction provides the operational details needed to carry out a levy and sale. When all three align, the sheriff can seize and sell eligible property.

Several factors ensure enforceability. The writ must be current and filed in the proper enforcement office. Your debtor must be correctly named, matching the judgment. The property must be in the county. The property must be personal property and not exempt. There must be equity after considering liens, security interests, and statutory exemptions. You must pay the enforcement fees and deposit. The direction must be complete and signed. If any of these fail, the sheriff may decline to act or may suspend the levy.

A writ in Small Claims Court is generally effective for six years. You can renew before expiry. If the writ lapses, the sheriff cannot proceed until you renew and refile. Priority between competing creditors is based on filing dates and, for personal property, may also be affected by prior secured interests. The sheriff will not resolve complex priority disputes. If a security holder claims priority, the sheriff will pause or release the asset unless there is clear surplus equity.

Exemptions apply. The law protects basic household furnishings, a portion of tools of the trade, and a portion of a motor vehicle’s value. Exemptions change over time and by category. The sheriff applies them by default. If an item is exempt, the sheriff will not seize it. If an item is partly exempt, only the non-exempt equity is available. If the debtor proves an exemption, the sheriff must respect it.

The sheriff also needs safe access and reasonable instructions. You cannot direct the sheriff to break into locked premises without lawful authority. The sheriff may require you to arrange entry with a landlord, property manager, or locksmith. The sheriff will not seize leased goods, consigned stock, or goods not owned by the debtor. If ownership is unclear, the sheriff may require proof of ownership or may request that you bring a motion for directions.

You remain responsible for fees and disbursements. The sheriff may require a deposit to cover towing, storage, locksmiths, advertising, and auction costs. These costs can be added to the amount the debtor owes. But if there is no sale or no surplus, your deposit may not be recovered. Provide clear, actionable targets to reduce wasted costs.

How to Fill Out a Form 20O – Direction to Enforce Writ of Seizure and Sale of Personal Property

Follow these steps to complete the form accurately and improve your chances of collection.

1) Confirm prerequisites

- Ensure you have a Small Claims Court judgment. Confirm the debtor’s exact legal name as it appears on the judgment.

- Ensure you have a Writ of Seizure and Sale of Personal Property issued and filed with the enforcement office in the county where the property is located.

- Check that the writ is still valid. Renew it if needed.

- Gather information about assets, addresses, and business locations. Note vehicle plates, VINs, and serial numbers if known.

- Calculate the current balance owing, including interest and any credits.

2) Identify the court and file

- Enter the court location and your Small Claims Court file number exactly as on your judgment and writ.

- Identify the enforcement office (the sheriff) where the writ is filed. The direction must match that office. If you plan to seize in more than one county, you need to file and direct in each office.

3) Creditor information

- Enter your name or your business’s legal name. Use the name on the judgment.

- Provide your mailing address, phone number, and email. The sheriff will contact you for logistics and costs.

- If you have a representative, list the firm or agent name and contact details.

4) Debtor information

- Enter the debtor’s full legal name, including middle names or initials, as shown on the judgment. Include any trade name or operating name. Example: “John A. Smith carrying on business as Smith Heating.”

- Provide the debtor’s last known residential address and phone if known.

- For corporate debtors, include the exact corporate name and any business number if you have it.

5) Amount owing

- State the judgment principal still unpaid.

- State the post-judgment interest rate that applies. If your judgment or contract sets a rate, use that rate. If not, use the default post-judgment rate.

- Calculate interest from the judgment date to the date of your direction. Show the calculation in a brief schedule if needed.

- Add costs you have been awarded and any enforcement costs claimed to date.

- Deduct any payments received. Show the net balance. The sheriff needs the collection target.

6) Describe the property to seize

- Give clear, specific descriptions. The sheriff cannot guess. List items like “2016 Ford F-150, grey, plate ABCD 123, VIN if known.” Or “Stihl MS 461 chainsaws, quantity 2, orange case.” Or “Restaurant inventory and equipment at 123 King Street, rear kitchen and storage.”

- If you do not know serial numbers, describe the location and appearance. Mention where on-site the items sit.

- If there are items you do not want seized, say so. This prevents unnecessary costs and disputes.

7) Provide locations for seizure

- Give exact addresses for each place to attend. Include unit numbers, yard descriptions, and access points.

- State business hours or times when the debtor or assets are present.

- If the entry requires coordination, add contact names for a landlord, manager, or superintendent.

- If the assets are mobile, suggest times and routes when the asset is usually present.

8) Vehicle-specific details

- Include plate numbers, VINs, make, model, colour, and parking spots. Ask the sheriff to check ownership if you are unsure. The sheriff may run a search to confirm title and liens.

- State whether the vehicle is often parked on a street or inside a garage. Street locations may help with timing.

9) Business assets and inventory

- If targeting a business, identify the legal owner of the assets. If the store’s name differs from the debtor’s name, explain the link.

- Give a general inventory list and a value estimate. The sheriff assesses whether seizure is worthwhile.

- Mention any known secured creditors. If you know of financing on equipment, note the lender. The sheriff will consider equity.

10) Exemptions and encumbrances

- Acknowledge that statutory exemptions apply. Do not direct seizure of clearly exempt items like basic household furniture.

- If the debtor is a sole proprietor, tools of trade may be partly exempt. Focus on higher-value, non-exempt items.

- If an item appears financed, note it. The sheriff may still attend to assess equity.

11) Special instructions

- Indicate any safety concerns, guard dogs, or alarm systems.

- Suggest using a locksmith if lawful entry is available through a landlord. The sheriff will decide on the method.

- Request priority timing if assets are at risk of being moved. The sheriff schedules within workload and legal limits.

12) Attach supporting schedules

- Attach a copy of the issued writ as filed in the enforcement office.

- Attach a copy of the judgment and any costs endorsements.

- Attach your interest calculation and payment history. Keep it clear and simple.

- Attach photos, maps, or sketches that help locate assets. Label each attachment as a schedule.

13) Fees and deposit

- Prepare to pay the enforcement fee and any required deposit for disbursements. Ask the enforcement office about current amounts.

- State in the form that you will pay towing, storage, locksmith, and advertising costs from your deposit. These may be added to the debtor’s total if recovered.

14) Signature and date

- Sign the form. If you are a corporation, an authorized officer or agent signs.

- Date the form. Use your full name in print below your signature.

- By signing, you confirm the information is true to your knowledge.

15) File and deliver the direction

- File the completed Form 20O with the same enforcement office that holds your writ. Keep a copy for your records.

- Provide all schedules and your deposit at filing. Incomplete directions slow enforcement.

16) Coordinate the levy

- After filing, respond quickly to calls from the sheriff. Confirm access arrangements and timing.

- Be ready to attend during the levy if requested. Your presence can help identify items and resolve access issues.

- If the debtor pays you directly to avoid seizure, notify the sheriff at once. Provide proof and ask to suspend if paid in full.

17) After seizure and sale

- The sheriff will store and advertise seized goods. Sales are often by auction.

- Sale proceeds pay sheriff’s fees and costs first. The balance goes to your writ, then to any other writs by priority. Surplus, if any, goes to the debtor.

- If proceeds do not cover your judgment, you can continue to enforce against other assets. You can issue further directions as long as your writ remains valid.

Practical tips as you complete the form:

- Use exact names. Match the judgment, including middle initials and operating names.

- Be specific. Vague descriptions lead to wasted trips and extra costs.

- Target equity. Choose items with value after liens and exemptions.

- Update as needed. If you discover new assets or addresses, file a new or amended direction.

- Keep communication open. Work with the enforcement office on logistics and fees.

By completing Form 20O with precise details, you give the sheriff a clear roadmap. You improve the odds of a successful levy and sale. You also manage your costs and time by focusing on assets that matter.

Legal Terms You Might Encounter

Judgment creditor means you, the party owed money under the court judgment. On this form, you direct enforcement. You choose how the enforcement office should act. You also confirm the balance still owing.

Judgment debtor means the party who owes you money. You identify the debtor on the form. Accurate names matter for seizure. Use the legal name from the judgment.

Writ of seizure and sale is the court order that lets the sheriff act. It authorizes seizure of non-exempt personal property. Your direction tells the sheriff how to use that writ.

Personal property means movable assets, not land. It includes vehicles, equipment, inventory, and tools. It can include household goods, subject to exemptions. Your direction should list target items if known.

Exempt property means property the law protects from seizure. Basic household items and some tools may be exempt. The sheriff applies these rules. Your direction should not target exempt items.

The enforcement office refers to the sheriff’s office that enforces writs. You file the writ and your direction there. It must be the office where the property is located.

Seizure is the act of taking legal possession of property. The sheriff can seize and arrange sale. Your direction triggers this process.

Sale proceeds are the money from the sale of seized property. The sheriff pays certain costs first. The balance goes toward your judgment. Your direction can ask for proceeds to be paid to you.

Third-party claim happens when someone else claims ownership of seized items. The sheriff may pause seizure. You may need to provide proof or accept a court process. Your direction should target items clearly owned by the debtor.

Stay of enforcement means a legal pause. It can follow a payment plan, appeal, or court order. If there is a stay, the sheriff will not act. Your direction should not be submitted if enforcement is stayed.

Levy means collect payment from the debtor’s property. Levy can mean seize cash on site or sale proceeds later. Your direction enables levy under the writ.

Priority means the order creditors get paid from proceeds. Liens and earlier writs may rank ahead of you. Your direction cannot change priority.

Costs and disbursements are the fees and expenses tied to seizure and sale. They include storage, towing, and advertising. The sheriff recovers these from sale proceeds before paying you.

FAQs

Do you need to file a new direction for each enforcement office?

Yes. File a direction with each enforcement office where the property sits. A writ only operates where filed. If the debtor has assets in multiple regions, file there as well. Submit a separate direction to each office so the sheriff can act locally.

Do you have to list specific assets on the form?

You do not have to, but it helps. The sheriff acts faster when you identify assets and locations. List vehicles with plate or VIN, or tools and inventory with make and model. Add hours for access, contact names, and security details. Specifics reduce wasted trips and costs.

Do you need to serve the debtor with the direction?

No. The direction is for the enforcement office. You do not serve it on the debtor. The sheriff will give any required notices during enforcement. Keep your copy, plus proof of filing and payment of fees.

Do you need to pay deposits or fees to the sheriff?

Often yes. Seizure and sale can require upfront deposits. Common costs include towing, storage, locksmiths, or advertising. Ask the office about current fee schedules and required deposits. Your deposit is usually recoverable from the sale proceeds if the assets sell.

Do you need to renew your writ before using this form?

Your writ must be valid and on file. If it has expired, renew it first. Check your writ’s issue date and any renewals. The sheriff will not act on an expired writ. Confirm status with the enforcement office before filing the direction.

Do you have to update the amount owing before you file?

Yes. State the current balance, including interest and allowed costs. Provide your calculation date. The sheriff needs a clear number to collect. Attach a simple calculation sheet if helpful.

Do you need to direct a seizure from a private residence?

You can, but entry rules apply. The sheriff respects privacy and safety laws. They may require access or coordinate with you. Provide clear directions, times when occupants are present, and contact details. The sheriff decides how and when to attend.

Do you have to act if the debtor offers a payment plan?

You choose. You can pause or withdraw your direction. If you accept a plan, tell the enforcement office in writing. Get payments in a traceable form. If the debtor defaults, you can reactivate enforcement.

Checklist: Before, During, and After

Before signing

- Confirm your writ status. Make sure your writ is valid and filed with the correct enforcement office. If you plan to enforce in a new region, file the writ there first.

- Verify debtor details. Use the legal name, business number (if any), and last known addresses. Include unit numbers and gate codes for access.

- Identify assets. List vehicles, equipment, inventory, or other personal property. Note serial numbers, VINs, makes, models, and locations.

- Estimate the amount owing. Update interest and allowable costs to a current date. Prepare a short calculation.

- Gather support documents. Keep a copy of the judgment, writ, renewals, and any previous enforcement. Collect any lien searches if done.

- Budget for deposits. Ask the enforcement office about required deposits and likely third-party costs. Arrange funds so you do not delay action.

- Plan access and timing. Confirm business hours, shift schedules, and site contacts. Plan how the sheriff can enter and identify assets.

- Check for exemptions and liens. Avoid targeting exempt goods. Identify likely liens or leases. Adjust your plan if equity seems low.

- Assign a contact. Choose a person who can answer the sheriff’s calls. Provide a phone number that will be answered.

During signing

- Verify names. Ensure your name and debtor’s name match the judgment and writ. Double-check spelling and legal entities.

- Confirm the court file number and writ details. Use the exact numbers shown on the writ. Avoid transpositions.

- State the amount owing as of a date. Add interest details if the form provides a field. Attach a calculation if space is tight.

- Give clear instructions. State what to seize, where, and any special directions. Ask the sheriff to contact you before incurring large costs.

- Choose the enforcement office. Identify the office that will act on the direction. Use the office where assets are located.

- Provide addresses with precision. Include unit numbers, yard locations, and cross-streets. Note locked areas and who has keys.

- Sign and date. Sign as the judgment creditor or authorized agent. Include your title and contact details.

- Include attachments. Add pages for asset lists, photos, maps, and calculations as needed. Label each attachment clearly.

After signing

- File with the enforcement office. Deliver the original direction and required copies. Pay the filing fee and any deposits.

- Provide proof of writ filing. If the writ was filed or renewed recently, include a copy. Confirm the writ is indexed for the debtor.

- Confirm receipt and next steps. Ask for a file or reference number. Request an estimated timeline for first attendance.

- Stay reachable. Keep your phone on and monitor email. Respond quickly to the sheriff’s requests or questions.

- Track expenses. Record deposits, disbursements, and invoices. You may recover these from sale proceeds if assets sell.

- Update balances. Adjust interest and costs as enforcement progresses. Keep a running ledger.

- Notify other stakeholders if needed. If you know of co-owners, landlords, or secured creditors, prepare to address claims. The sheriff will manage notices as required.

- Store records securely. Keep copies of all filings, receipts, and communications. You may need them for distributions or disputes.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Don’t forget to file the writ in the right place. If the writ is not filed in the enforcement office where assets sit, the sheriff cannot act. You will lose time and pay duplicate fees.

Don’t list vague targets. “Seize all assets” is not helpful on its own. The sheriff may make a fruitless visit. Name items, locations, and identifiers to improve results.

Don’t ignore exemptions and liens. Seizing exempt goods or heavily encumbered items wastes money. You risk storage and towing charges with no net recovery.

Don’t underfund deposits. If you do not post required deposits, enforcement stalls. Delays can let assets move or depreciate.

Don’t overstate the amount owing. Inflated amounts trigger disputes and delays. Use a clear interest calculation and the correct rate.

What to Do After Filling Out the Form

File the direction with the correct enforcement office. Attach any required copies and your updated balance. Pay the filing fee and any deposits. Request written acknowledgment with a reference number.

Coordinate early. Ask the sheriff when the first attendance will occur. Offer practical details: access points, security contacts, and best times. Confirm how the office prefers to handle high-cost steps. Set a threshold for new expenses that requires your approval.

Prepare for contingencies. Get ready for third-party claims, exemptions, or locked premises. Keep proof of the debtor’s ownership. Have alternative targets if primary items are not available.

Monitor progress. Follow up politely if you do not hear back by the estimated date. Provide any newly discovered asset locations. If an address changes, tell the sheriff immediately.

Manage payments and settlements. If the debtor pays you directly, give written updates to the enforcement office. Tell the office to pause or withdraw action if needed. Keep a precise ledger. Provide receipts so the sheriff can adjust the balance.

Handle amendments. If you need to add assets or change instructions, file a fresh direction or a written update as accepted by the office. Reference the same writ and enforcement file number. Keep your instructions consistent and clear.

Consider parallel steps. A writ against personal property can run alongside other remedies. You may also register the writ where land may exist, or consider garnishment if appropriate. Use the tools that fit your situation and timing.

Review costs and expected recovery. Confirm towing, storage, locksmith, and advertising estimates. Decide if anticipated net proceeds justify continued action. If likely net is low, adjust your plan.

Manage sale logistics. If the sheriff seizes items, they will arrange sale. The office handles advertising and auction details. Ask for notice of sale timing, so you can monitor and assist with information that improves value.

Request distribution of proceeds. After the sale, the sheriff accounts for costs. The office applies proceeds based on priority. Ask for a statement of distribution and the remaining balance owing. If you are paid in full, confirm closure of the file.

Maintain your writ. If your judgment is not fully paid, track the writ’s expiry date. Renew in time to preserve enforcement rights. A lapsed writ pauses your options until renewed.

Close the loop. Once satisfied or settled, notify the enforcement office to close the file. Keep all final statements, receipts, and correspondence. Update your internal records and mark any next renewal dates.

Keep compliance in mind. If a court stays enforcement or an appeal is underway, tell the sheriff. Do not instruct action during a stay. Provide the order to avoid unnecessary steps and costs.

Evaluate outcomes. After enforcement, review what worked and what did not. Refine your asset identification, timing, and instruction templates. This improves future recoveries and reduces avoidable costs.

If you need to withdraw. Send written instructions to the enforcement office. Ask for an up-to-date accounting of costs and any refundable deposit. Confirm that the file is closed.

Plan follow-up enforcement. If assets were not found, set reminders. New assets can appear later. You can file an updated direction when you learn of new property. Keep monitoring.

A note on timing. Seizure and sale take time. Access, notices, and logistics affect pace. Regular, concise updates help the sheriff act efficiently. Your cooperation speeds resolution.

Final documentation. When the file closes, save everything. Store the judgment, writ, directions, receipts, and distribution reports. These records protect you if questions arise later.

Disclaimer: This guide is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as legal advice. You should consult a legal professional.