Third Party Letter of Authorization

Fill out nowJurisdiction: Canada | Ontario

What is a Third Party Letter of Authorization?

A Third Party Letter of Authorization is a signed letter. It gives a named person or company permission to act for you on a defined matter. It allows them to get information, complete tasks, and speak to others on your behalf. It does not hand over full control of your affairs. It grants only the powers you list in the letter.

You use this form to create a limited agency. You remain the decision maker. Your representative acts within the scope you set. Their authority is narrow. It is also temporary. You choose when it starts and when it ends.

Who typically uses this form?

Individuals use it to let someone handle a file or pick up documents. Tenants and landlords use it to manage viewings, keys, or repairs. Small businesses use it to let a bookkeeper or consultant speak to an account manager. Corporations use it to authorize employees, vendors, or advisors to interact with vendors, regulators, or service providers. Professionals use it to allow staff to obtain records or submit forms.

Why would you need this form?

You may not be available to attend in person. A vendor may ask for written consent before discussing your account. A government office may require proof before releasing information. Privacy laws require clear consent. A simple letter meets that need. It also prevents delays. Your representative can move the matter forward without you present.

Typical usage scenarios

You can authorize a contractor to access a unit and speak with a building manager. In utilities, you can permit a consultant to open, close, or move an account. In insurance, you can authorize a broker to discuss a claim and receive updates. In tax matters, you can allow an accountant to ask questions about an assessment. In corporate settings, you can let a team member sign for deliveries and request service tickets. In licensing, you can authorize a representative to submit forms and pick up permits. In litigation support, you can allow a clerk to obtain copies of records or file materials.

A Third Party Letter of Authorization is not a power of attorney. It does not grant broad legal authority. It does not let someone sell property or sign major contracts unless you state that power clearly. Many institutions will not accept it for high‑risk actions. It is best for defined tasks and information access. It is short, practical, and purpose‑built.

When Would You Use a Third Party Letter of Authorization?

You use this letter when someone else needs to interact with a specific counterparty for you. You also use it when a counterparty refuses to speak with anyone else without consent. The letter gives that consent in writing. It sets the boundaries and duration.

As a tenant, you may authorize a friend to pick up keys. You may also authorize a contractor to coordinate entry with your property manager. As a landlord, you may authorize a property manager to handle rent issues and unit access. You may also allow a superintendent to discuss repairs with a contractor. In both cases, the letter prevents privacy or access disputes.

As a business owner, you may authorize your accountant to discuss your file with a tax agent. You may also authorize a payroll provider to correct filings. You may permit an IT vendor to speak to a software support desk. You can also authorize a consultant to request invoices and account histories. Many service providers will require this letter before sharing account details.

As a corporate officer, you may authorize an employee to deal with a regulator or licensing office. You can allow them to submit forms, pick up permits, or pay fees. You can also authorize a customs broker to receive shipment documents. You may permit a facilities manager to speak with utilities and schedule site visits.

As an individual, you may authorize a family member to deal with a repair shop. You may allow them to pick up your vehicle and sign for work within a set budget. You may authorize a friend to submit an application at a government counter when you cannot attend. You may also authorize a representative to obtain copies of records.

As a law firm or professional office, you may use a letter to let a staff member collect records. You may also authorize a process server to file or pick up materials. The letter confirms their link to your client or your firm. It reduces pushback at service counters.

You also use this letter when time matters. Phone tags and privacy checks can slow work. A clear authorization lets your representative proceed. It reduces delays and repeated calls. It also sets a paper trail that protects you and the recipient.

Finally, you use this letter when the counterparty has no standard form. Many organizations have their own forms. When they do not, a well‑drafted letter fills the gap. It shows your consent and the scope of authority. It is simple to prepare and update.

Legal Characteristics of the Third Party Letter of Authorization

A Third Party Letter of Authorization is legally binding between you and your representative. It forms an agency appointment. You, the principal, grant authority to the agent for defined tasks. The agent agrees to act within those limits and follow your instructions. If the agent acts within their authority, you are usually bound by those acts. If the agent exceeds their authority, you can dispute those acts.

The letter is also evidence of your consent to disclosure. Privacy laws require clear, informed consent before releasing personal information. Your letter, when clear and specific, satisfies that consent. It tells the recipient who may receive information and about what. It may not compel a recipient to accept it. However, it gives them a defensible basis to speak with your representative.

Enforceability comes from clarity and proper execution. The letter should name the parties with full legal names. It should describe the powers in plain language. It should set start and end dates. It should include your signature and the date. For businesses, it should include the signer’s title and authority. Many recipients will also ask for a copy of photo identification. Some may require a witness or notarization. Those are not always legally required. They are policy checks used by recipients to reduce risk.

The letter cannot grant powers you do not have. If a statute or policy requires a specific form, your letter may not replace it. For example, transfers of land, certain banking actions, or regulated filings may demand prescribed forms. Your letter will not override those rules. A recipient can refuse to act on a letter that does not meet their requirements.

Electronic signatures are generally valid for most day‑to‑day authorizations. Some recipients still require a wet ink signature. Always confirm their acceptance. If in doubt, sign in ink and provide a scanned copy and the original by mail or in person.

You can revoke the letter at any time. To revoke, send written notice to your representative and each recipient. Ask them to acknowledge receipt. Keep proof of delivery. Revocation does not undo actions already taken within the prior authority. It stops new actions going forward.

You can limit your risk through clear limits. State what the agent can do and cannot do. For example, you can allow inquiries but forbid commitments. You can allow document pickup but forbid signing contracts. You can set a dollar cap for any payment or expense. You can also require your approval for specific steps.

The governing law should be Ontario. This confirms the legal framework for the authorization. It helps resolve disputes. It also signals the expected standards for consent and agency.

How to Fill Out a Third Party Letter of Authorization

Follow these steps to prepare a clear, accepted letter.

1) Set the title and date.

- Use a clear title, such as “Third Party Letter of Authorization.”

- Add the date of signing at the top right or below the title.

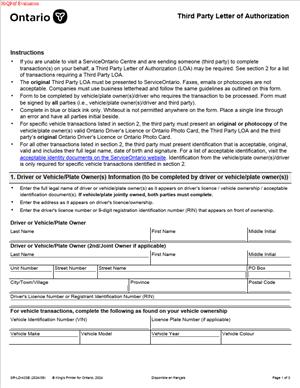

2) Identify yourself as the principal.

- For individuals, list your full legal name and address.

- Include your phone number and email.

- For businesses, use the exact legal name and address.

- Add your business number if relevant.

- Identify the signing officer by name and title.

- Confirm the signer has authority to bind the business.

3) Identify the authorized representative.

- List their full legal name.

- Add their company name if they act through a company.

- Include their address, phone, and email.

- Add a government ID type and number if needed.

- Do not include a copy of the ID in the letter body.

- Instead, attach it as a schedule if requested.

4) Identify the recipient or counterparties.

- Name the organization(s) the representative will deal with.

- If you have several, list them in Schedule A.

- Include account numbers, file numbers, or addresses.

- Be precise to help the recipient locate your file.

5) Define the purpose and scope of authority.

- Write the purpose in one or two sentences.

- Example: “To allow inquiries and updates on account 12345.”

- Then list permitted actions in clear terms.

- Keep the list specific and narrow.

- Typical permitted actions include:

- Make inquiries and receive information.

- Request and receive copies of documents.

- Submit forms and supporting documents you provide.

- Pick up permits, keys, or records.

- Schedule inspections, service calls, or appointments.

- If the representative will sign documents, name the documents.

- State the limits of any signing power and the dollar cap.

- If payments are allowed, set a maximum amount and purpose.

- If you do not want any commitments, say so plainly.

6) State prohibited actions.

- Include a short paragraph of exclusions.

- Example: “This authorization does not permit contract execution, settlements, or admissions.”

- Add any other limits that fit your case.

- Prohibitions help avoid misunderstandings.

7) Include consent for information disclosure.

- Authorize the recipient to release information to the representative.

- Describe the type of information, such as account details or status.

- If sensitive data is involved, name it clearly.

- Explain that the consent lasts only for the duration of the letter.

8) Set the duration.

- State the start date and time.

- State the expiry date and time.

- You can also tie expiry to an event.

- Example: “This authorization ends upon permit issuance.”

- Avoid open‑ended durations unless necessary.

- A window of 3 to 12 months is typical.

- Shorter periods reduce risk.

9) Add conditions on how the representative must act.

- Require them to show ID when using the letter.

- Require them to keep information confidential.

- Require them to follow your instructions.

- State they cannot delegate without your written consent.

- Ask them to keep records of actions taken.

10) Allocate responsibility and limits.

- State that you remain responsible for fees or charges you approve.

- State that the representative cannot incur costs beyond set limits.

- If you want an indemnity from the representative, state it.

- Keep the language simple and specific.

11) Set revocation terms.

- Reserve your right to revoke at any time.

- State that revocation must be in writing.

- State that revocation is effective when delivered to the recipient.

- Ask the recipient to stop acting on the letter after notice.

- Confirm that prior valid acts remain effective.

12) Choose governing law and venue.

- State that the letter is governed by Ontario law.

- If you expect disputes, select a venue, such as your city.

- This adds clarity for everyone.

13) Add schedules for clarity.

- Schedule A: List recipients, account numbers, file numbers, or property addresses.

- Schedule B: List documents the representative may sign or collect.

- Schedule C: Include copies of ID for you and the representative if requested.

- Schedule D: Include any extra limits, budgets, or instructions.

14) Prepare the signature blocks.

- For individuals:

- Add a signature line, printed name, and date.

- Add a witness line if the recipient requires one.

- Use a witness who is not the representative.

- For businesses:

- Add the company’s full legal name above the signature line.

- Add the signer’s name and title.

- If you use a corporate seal, place it by the signature.

- If two signatures are required by policy, add a second line.

- Consider adding an acknowledgment by the representative.

- They accept the limits and duties.

- They agree to show ID and act in good faith.

- Consider a recipient acknowledgment when practical.

- They confirm they have received and will rely on the letter.

- This is optional and often not needed.

15) Execute the letter.

- Sign in blue or black ink.

- Date each signature.

- If a witness is used, have them sign and print their name and contact.

- If notarization is requested, arrange it before sending.

- Keep the letter clean and readable.

16) Deliver the letter.

- Ask the recipient how they prefer to receive it.

- Common options include email, portal upload, fax, or in person.

- Send a clear scan if delivering electronically.

- If mailing, use a tracked method when timing matters.

- Include schedules and ID copies if requested.

- Ask for a written confirmation of acceptance.

17) Keep records.

- Keep a signed original in your files.

- Save PDFs of the letter and schedules.

- Record when and how you delivered it.

- Note the acceptance date and any conditions imposed.

18) Monitor and follow up.

- Confirm that your representative can access the file.

- Do a quick test call if time allows.

- Remind your representative of the limits and expiry date.

- Renew or revoke the letter as your needs change.

Practical drafting tips help reduce friction. Use plain language. Avoid broad phrases like “any and all acts.” Replace them with clear tasks. Name the accounts, files, or properties. Set a realistic expiry. Add a short buffer if delays are possible. For example, set expiry 30 days after the expected completion date. Avoid granting signing authority unless necessary. If you must, describe the specific form or document.

Consider risk and identity checks. Many recipients will not release sensitive data without ID. Expect them to call you to confirm the letter. That is normal. If you need fast action, tell the recipient you expect confirmation calls. Provide a direct number and call window in the letter.

Be ready for organization‑specific forms. Some recipients will ask you to sign their form as well. Treat your letter as the umbrella. Complete their form to meet their policies. Keep the scope consistent across both documents.

Think about conflicts and errors. If two letters conflict, the latest one should govern. You can state that in your letter. Example: “This authorization supersedes prior authorizations on this matter.” Also add a clause that errors in account numbers do not void the authorization if the context is clear. Precision still matters, so check for typos.

Finally, protect your privacy. Include only what the recipient needs to identify your file. Avoid listing unrelated accounts. If you need to authorize access to several unrelated accounts, create separate letters. Smaller scopes reduce risk and ease acceptance.

By following these steps, you create a clear, useful letter. Your representative can act without delay. The recipient can share information confidently. You stay in control with defined limits and timelines. That is the purpose of a Third Party Letter of Authorization.

Legal Terms You Might Encounter

Principal means you. You are the person or business granting authority. In this form, you state your name, contact details, and the scope of permission you give. You also confirm you can grant that permission.

Authorized representative means the person or company you appoint. Some forms call them an agent. This is the third party who can act for you. You name them clearly and describe what they can do and for how long.

Scope of authority describes the exact tasks the representative can perform. It limits what they can do. In this form, you list activities, accounts, or files they can access. If it is not written in the scope, they cannot do it.

Purpose explains why you are granting authority. It helps the receiving organization process the form. Write the purpose in plain words. Example: “access account records to verify outstanding balance.”

Duration (or term) sets the start and end of the authority. You can state a specific end date or an event that ends it. The receiving organization may expect an expiry. Include one if they do.

Revocation means you are canceling the authority. You can revoke at any time unless you have agreed otherwise. In this form, you can include how you will revoke and who you will notify. A written revocation is best.

Consent to disclose covers your permission to share your information. Without clear consent, organizations may refuse disclosure. In this form, you identify which information can be shared and with whom. Include limits you want.

Identification and verification refer to how identities are confirmed. Organizations often need proof of identity to accept the form. You may need to include ID details or attach copies. Your representative may also need to verify identity when using the letter.

Witnessing and notarization are methods to confirm the signature. A witness observes your signing and signs too. Notarization involves a notary who verifies identities and signatures. Some organizations require one or both. Others accept a standard signature.

Electronic signature means you sign digitally rather than with ink. Many organizations accept secure e-signatures. Some still require original ink signatures. Check what the receiving organization will accept before you sign.

FAQs

Do you need to notarize the letter?

Not always. Many organizations accept a signed letter with a witness. Some require notarization for sensitive access or high-value transactions. Ask the receiving organization what they require. If they accept notarization or witnessing, follow their format exactly.

Do you need to include an expiry date?

It is a good idea to include one. Many organizations expect a clear end date. It protects you and keeps access current. If you do not include an expiry, they may reject the letter or treat it as valid for a short period only. Set a date that fits the task.

Do you need to list account numbers or file references?

Usually, yes. Clear identifiers help the organization act quickly and avoid errors. Include account numbers, reference numbers, or file names that match their records. If you do not know them, ask for guidance on acceptable identifiers.

Do you need a separate letter for each organization?

Often, yes. Most organizations require a letter addressed to them. The letter must meet their rules and include their reference details. If multiple organizations are involved, prepare a tailored letter for each one to avoid rejection.

Can you authorize more than one representative?

Yes. You can name more than one person or company. State if they can act together or independently. Define the scope for each one if their roles differ. Keep it clear to avoid confusion or overreach.

Can you use an electronic signature?

Many organizations accept a secure electronic signature. Some need an original ink signature or a notarized copy. Ask how they accept documents. If you use e-sign, include date and time stamps and keep a copy of the certificate or audit trail.

Can you limit what the representative can see or do?

Yes. You can limit access to specific files, dates, or actions. Write those limits in the scope. For example, you can allow “view-only access” or “authority to request statements but not make changes.” The organization will follow the written limits.

How do you revoke the authorization?

Send a signed revocation notice to the organization and the representative. Include the original authorization date, the representative’s name, and the effective revocation date. Ask the organization to confirm in writing that access has ended. Keep proof of delivery.

Checklist: Before, During, and After the Third Party Letter of Authorization

Before signing

- Confirm the exact purpose and tasks you want to authorize.

- Gather the receiving organization’s formatting or submission rules.

- Collect account numbers, client IDs, or file references.

- Confirm the representative’s full legal name and contact details.

- Obtain copies of identification if the organization requires them.

- Decide the start date and expiry date.

- Define clear limits on scope and information access.

- Decide if witness or notarization is required and arrange it.

- Confirm if electronic signatures are acceptable.

- List any attachments you need to include.

- Prepare a revocation plan and contact list for notices.

- Choose how you will deliver the letter (mail, in person, online).

- Set internal approval if you sign for a business or practice.

- For businesses, confirm signing authority and title.

During signing

- Check your name and address match your identification.

- Check the representative’s name is correct and complete.

- Confirm the receiving organization’s name and address are correct.

- Review the scope sentence. Make it specific and unambiguous.

- Insert start and end dates. Avoid blank spaces.

- Add any required account or file references.

- Include consent wording for disclosure of specific information.

- Cross out any optional clauses you do not accept. Initial changes.

- Sign with the correct date. Use your legal signature consistently.

- Ensure the witness or notary signs and dates, if required.

- Initial each page if the organization requires it.

- Attach required copies of identification or supporting documents.

- Label attachments and reference them in the letter.

- Keep a clean copy for your records before sending.

After signing

- Send the letter to the receiving organization using the approved method.

- If delivery is online, upload in the correct file format.

- If delivery is by mail or courier, keep the tracking number.

- Provide a copy to your representative so they can act.

- Ask the organization to confirm acceptance and any conditions.

- Record the date sent and who received it.

- Set a calendar reminder for the expiry date.

- Monitor your accounts and files for authorized activity only.

- Store the signed letter and proof of delivery securely.

- If details change, prepare and send an updated letter.

- Revoke promptly when the task is complete or if trust changes.

- Update your internal records and stakeholders as needed.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Vague scope of authority.

If you say “handle my affairs,” the organization may reject the letter. Or your representative could overreach. Don’t forget to list precise tasks, files, and limits.

Missing expiry date.

Without an end date, some organizations will not accept the letter. Others may treat it as open-ended, which increases risk. Set a clear end date that fits the purpose.

Wrong names or identifiers.

Typos in names or account numbers cause delays and refusals. Double-check spelling, IDs, and reference numbers. Confirm they match the organization’s records.

Using the wrong signature format.

Some organizations require ink signatures, witnesses, or notarization. If you skip a required step, they will not act. Confirm requirements before signing.

Forgetting to revoke.

If the project ends but the letter remains valid, access may continue. That can lead to unwanted disclosure. Send a written revocation and confirm it is in effect.

What to Do After Filling Out the Form

Submit the letter following the organization’s rules. Use their portal, email channel, mail, or in-person delivery as directed. Include any required attachments. Keep proof of submission.

Confirm acceptance. Ask for written confirmation that the letter meets their requirements. Note any limitations they apply. Share this confirmation with your representative.

Brief your representative. Explain the scope, limits, and expiry date. Provide relevant reference numbers and contact details. Remind them to present identification when acting.

Track activity. Monitor accounts or files for the actions you authorized. Keep notes of dates, contacts, and outcomes. Address any issues early with the organization.

Amend if needed. If the scope or dates need changes, issue a new letter. Mark the new letter as an amendment and reference the original date. Send it through the same submission channel.

Renew before expiry. If the task continues past the end date, prepare a renewal. Use updated dates and confirm any new requirements. Submit early so access does not lapse.

Revoke when done. Send a revocation notice to the organization and the representative. Include the original letter date and the effective revocation date. Ask for confirmation of revocation.

Store records securely. Keep copies of the signed letter, proof of delivery, acceptance, and revocation. Retain them for your retention period. Secure any identification documents you collected.

Review your process. Note what worked and what caused delays. Update your internal checklist for next time. This reduces effort and avoids repeat mistakes.

Disclaimer: This guide is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as legal advice. You should consult a legal professional.