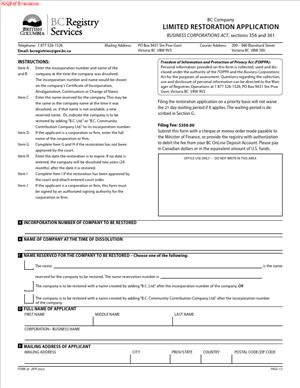

Form 28 – Limited Restoration Application

Fill out nowJurisdiction: Country: Canada | Province/State: British Columbia

What is a Form 28 – Limited Restoration Application?

A Form 28 – Limited Restoration Application is the document you use to bring a dissolved British Columbia entity back to legal life for a short time and for a specific purpose. You do this when you do not need a full revival. You only need the entity active long enough to complete one task. For example, you might need to transfer a property, finish a deal, or start or defend a lawsuit.

Why would you need this form?

You use this form when a company, society, or similar entity was dissolved and can no longer act. Dissolution cuts off the entity’s legal capacity. It cannot hold property, sign documents, sue, or be sued. In many cases, any property in the entity’s name will have vested in the government on dissolution. Limited restoration gives you a narrow window to fix a specific issue without the cost and burden of a full restoration.

Who typically uses this form?

This form is typically used by people with a direct stake in the outcome. You may be a former director, officer, or shareholder who needs to complete an unfinished transaction. You may be a creditor who needs to start or continue a claim. You may be a buyer or seller stuck because a dissolved entity’s name still appears on a land title or a mortgage. You may be a plaintiff who needs the dissolved company restored so you can serve your claim. Insurers, lenders, receivers, and court-appointed representatives also use limited restoration to validate discrete steps.

You would need this form when you discover the dissolved status is blocking a single action. If the entity must resume ongoing operations, file multiple back filings, or carry on business, limited restoration is not the right tool. In that case, you would look at a full restoration or revival. Limited restoration is targeted, short, and purpose-built. It is often faster and cheaper than a full restoration because you confine it to a defined act and a fixed time period.

Common usage scenarios include transferring or discharging a mortgage registered to the dissolved entity, signing a release in a settlement, assigning an asset, receiving or paying a refund tied to the entity’s name, or taking or defending one step in litigation. It is also used to correct a historical filing, update a register, or file a single overdue return required for a transaction, provided the purpose is narrow.

When Would You Use a Form 28 – Limited Restoration Application?

You use a limited restoration when you face a legal or transactional roadblock caused by dissolution, and only a discrete act is needed to clear it. Imagine you are selling a property and the title shows a mortgage granted by a company that no longer exists. The land title office will not accept a discharge signed by a non-existent entity. A limited restoration allows that company to exist just long enough to execute the discharge. Once done, the company dissolves again, and the title can transfer cleanly.

Consider litigation. You may need to sue a dissolved company for a pre-dissolution debt, or you may need to continue a lawsuit against it. Without restoration, you cannot start or continue a claim because there is no legal person to serve. Limited restoration lets you bring the entity back so you can serve your claim, seek judgment, or approve a settlement. The restoration order will say it exists only for the litigation steps you list, and only for a set time. After that, it dissolves again.

Creditors and lenders also use limited restoration to enforce or release security. If a general security agreement names the dissolved company as grantor, you may need the company temporarily restored to acknowledge payment and discharge the registration. The same applies to assignments, novations, and consents required to complete a sale of assets or a restructuring that references the dissolved entity.

Former directors, officers, and shareholders use limited restoration to complete housekeeping that requires the entity’s legal capacity. That could include transferring a vehicle, endorsing a cheque, or correcting a registry record. If the dissolved entity held money in trust or was due a refund, the payer may require the entity’s signature on a receipt or release. Limited restoration gives you that signature authority without reopening the entity’s business.

You also use limited restoration when you discover after the fact that the entity’s name appears on a contract that must be amended or terminated, or on a permit or licence that must be surrendered. If the action is narrow and time-limited, limited restoration is the right fit. If you instead need to resume operations, sign multiple new contracts, hire staff, or engage in ongoing business, you should not use a limited restoration. That is beyond its scope.

Typical users include buyers and sellers in real estate closings, litigants and insurers in active claims, lenders and secured parties, court officers and estates handling past obligations, and former managers who must complete a single pending act. The key is whether a single, well-defined act will solve the problem. If yes, a limited restoration is usually the most efficient route.

Legal Characteristics of the Form 28 – Limited Restoration Application

A limited restoration is legally binding because it is granted under governing corporate legislation and, where required, by court order. Once the registrar accepts the application or the court orders restoration, the entity regains legal status for the stated period and purpose. During that window, the entity can validly do the acts described in the order or approval. Third parties can rely on the signatures and steps taken within that scope.

What ensures enforceability?

Enforceability comes from two elements. First, the restoration instrument reactivates the entity’s legal personality. Second, it strictly limits that reactivation to specific acts and a defined time. The order or approval will say what the entity can do and for how long. If you act within that scope and timeline, the act is effective as if the entity had never been dissolved for that purpose. If you act outside of it, you risk invalid action.

Courts and the registrar expect a focused purpose and a realistic timeline. They will look for a clear reason why a full restoration is not necessary. They may require you to notify interested persons, such as former directors or shareholders, or affected creditors. If the entity held land or registered property, you may need to serve parties with registered interests. If there is a related court proceeding, the court may require a draft order that tracks the limited purposes closely.

The order may also deal with property that vested in the government on dissolution. In many cases, the order or approval will state that the property revests in the entity for the limited purposes. That way, the entity can transfer or release it. After the limited period ends, any remaining property will follow the default vesting rules again. This is why your description of the limited purpose must be precise. If the property needs to move, say so in the application and draft order.

A limited restoration does not relieve the entity of past liabilities or create ongoing rights. It does not revive the business broadly. It does not allow you to enter new business transactions beyond the limited purposes. You should not use it to avoid obligations. It is a narrow tool to fix a specific problem that cannot be solved while the entity is dissolved.

Time is central. The order will set a period, often measured in days or months. When the period ends, the entity is dissolved again automatically unless the order says otherwise. You must complete the targeted act before expiry. If you need more time, you must seek an extension before the period ends. An expired order cannot be used for fresh acts, and you may need a new application.

How to Fill Out a Form 28 – Limited Restoration Application

Follow these steps carefully. Precision matters. Your goal is to present a focused, justified request that the registrar or the court can grant without confusion.

Step 1: Confirm that a limited restoration fits your purpose.

- Make sure a single, specific act will solve your problem. Examples include transferring a property, discharging a registered interest, serving or defending a claim, or signing a release. If you need to carry on business or file a series of outstanding returns, you likely need a full restoration instead.

Step 2: Gather core details about the dissolved entity.

- You need the legal name at the time of dissolution, the incorporation or registration number, and the date of dissolution. If the name has since been taken by another entity, that is fine for a limited restoration. You are not renaming or relaunching the business. You will also need the last known registered office address and the names of the last directors or the last authorized signing officers.

Step 3: Identify yourself as the applicant and explain your standing.

- State your full legal name, address, and contact details. Describe your relationship to the dissolved entity and why you have an interest. For example, say you are a former director, a creditor, a purchaser under a contract, or a plaintiff in a claim. Keep it factual and tight. The registrar or the court needs to see that you are a proper person to bring this application.

Step 4: State the limited purpose with precision.

- Describe exactly what the entity needs to do while restored. Use simple verbs and avoid broad language. For example, say “execute and register a discharge of mortgage number [number]” or “accept service and defend Supreme Court action number [number].” If land or registered personal property is involved, include the legal description or registration number. If you need to transfer or release property that vested in the government, say so directly.

Step 5: Set a reasonable time period.

- Ask for the minimum time you need to complete the limited act. Common periods are 30 to 90 days. Explain why that period is required. For example, filings at the land title office can take time to process, or court timelines dictate response dates. Do not ask for an open-ended period. A tight timeline makes approval more likely.

Step 6: Provide supporting facts and documents.

- Attach evidence that shows the need and supports your standing. This often includes a copy of the certificate of dissolution or a registry search, a land title search, the affected security registration, the draft pleading, a settlement agreement, or a draft discharge or transfer. If others are affected, include proof of notice or their written consent. If you are asking to deal with property, include proof that the property was in the entity’s name at dissolution.

Step 7: Complete the parties section of the form.

- The parties are the applicant and the dissolved entity. Identify the dissolved entity by its full legal name and number. Identify the applicant by name and role. If there are additional interested persons you plan to serve or notify, list them in a schedule. Include last known addresses for service where you can.

Step 8: Draft the relief clauses clearly.

In the clauses section, set out the exact orders or approvals you seek. Use short, numbered paragraphs. Include these elements:

- An order restoring the entity for a limited period ending on a specific date.

- A statement limiting the entity’s powers to the listed purposes only.

- If needed, a clause revesting identified property in the entity during the limited period, solely to complete the listed acts.

- If litigation is involved, a clause allowing the entity to accept service and defend or prosecute the named action.

- Authority for named individuals to sign documents on the entity’s behalf.

- A clause that the entity is deemed dissolved again at the end of the period without further steps.

- Directions on costs if relevant, usually each party bearing its own costs for the application.

Keep the language tight. Do not include broad powers such as “carry on business” or “enter any contracts.” That risks rejection.

Step 9: Address notice and service.

- In your application, explain who you have notified or will notify. This may include former directors and shareholders, known creditors, and any person with a registered interest affected by the act. If the entity’s property vested in the government, explain how you are addressing that within the limited restoration. Attach proof of service or consent as a schedule. If you could not locate someone, describe your efforts.

Step 10: Sign and date the application.

- The applicant signs. If you are represented by counsel, counsel may sign as agent, and you still provide your details. Use your full legal name. The signature confirms the facts are true to the best of your knowledge and belief. Include the date and place of signing. If the process requires an affidavit or declaration, sign that before a commissioner or authorized person, and attach it as a schedule.

Step 11: Prepare the schedules.

Organize your attachments and label them clearly. Typical schedules include:

- Schedule A: Corporate registry search and certificate of dissolution.

- Schedule B: Evidence of the limited purpose (e.g., land title search, security registration, draft discharge).

- Schedule C: Copies of pleadings or draft pleadings if litigation is involved.

- Schedule D: Proof of notice, service, or consents.

- Schedule E: Draft order setting out the limited restoration terms.

Cross-reference each schedule in the body of your application where relevant.

Step 12: Review for scope and consistency.

- Check that the purpose, timeline, and relief clauses match. Confirm that names and numbers are consistent across the form and schedules. Make sure every requested power ties back to the listed limited purpose. Remove any vague or unnecessary language. Tight drafting reduces questions and delays.

Step 13: File and pay the fee.

- Submit the completed form with all schedules and the required fee. Keep proof of filing and payment. If the process involves a hearing or desk review, note the timeline and any next steps. If the registrar requests more information, respond quickly and provide the requested documents.

Step 14: If a hearing is required, be ready to explain necessity and scope.

- Bring clean copies of your application and schedules. Be prepared to explain why a limited restoration is the right remedy and why the timeline is tight but realistic. Confirm that you notified those affected. If the decision maker suggests narrower language, accept reasonable limits. The goal is a focused order that works.

Step 15: After approval, complete the limited act promptly.

- Once the order or approval issues, act fast. Sign and file the discharge, transfer the property, serve or file the pleadings, or sign the settlement documents. Keep dated copies of everything done under the limited authority. If land or security interests are involved, confirm registrations have completed.

Step 16: Handle follow-up filings.

- Some steps require you to file the order or approval with a registry that maintains the affected records. Do that without delay. If the order requires you to return for proof of completion, diarize the date and file the proof. If you need more time than expected, apply for an extension before the period ends. Do not let the deadline pass.

Step 17: Close the loop.

- When the period ends, the entity dissolves again automatically. Confirm that all intended acts are completed and registered. Notify any interested persons that the limited restoration has ended and provide copies of completed filings if requested. Keep a complete file, including the application, order, evidence, and proof of completion, in case questions arise later.

Practical tips

- Keep your purpose narrow and your timeframe short. This increases your odds of quick approval.

- Tie every requested power to a specific document or action.

- Use correct legal descriptions and registration numbers for land and security interests.

- If litigation is involved, include the exact court file number and style of cause.

- If you need authority to sign, name the specific signer and their role during the limited period.

- If property vested in the government, ask for revesting solely for the listed acts, and only for identified property.

By approaching your Form 28 this way—focused purpose, solid evidence, tight timelines—you set yourself up for a smooth approval and a clean, effective result.

Legal Terms You Might Encounter

- Limited restoration means bringing a dissolved company back into legal existence for a short, defined period to complete specific tasks. In the Form 28 – Limited Restoration Application, you state exactly what those tasks are and how long you need. The company is not fully revived. It can only do what the form and any related order permit.

- Dissolution is the legal end of the company. It may happen for missed filings, by request, or by administrative action. Form 28 exists because sometimes you need the company back temporarily after dissolution to transfer property, finish a lawsuit, or correct records.

- Registrar refers to the government office that keeps the corporate register. You submit Form 28 to that office or follow its filing directions. The registrar decides if your application is complete, collects fees, and records the limited restoration if approved.

- Corporate number is the company’s unique identifier. It ties your application to the right dissolved entity. On Form 28, you must list the exact number and the exact legal name used before dissolution to avoid delays.

- Registered office and records office are the official addresses on file. Form 28 asks for current addresses for service and records during the limited restoration. You must provide a physical address within the province for delivery of legal documents and access to records if required.

- Specific purpose describes what you want the restored company to do. This is central to Form 28. Examples include disposing of an asset, assigning a contract, or defending or settling a claim. Your wording must be narrow and clear. If the purpose is vague, your application can be refused or restricted.

- Restoration period is the limited time you request for the company to exist again. On Form 28, you set a start (often the approval date) and an end date. The period must be long enough to complete the tasks, but not longer than necessary. Once it ends, the company dissolves again unless you extend or convert to a full restoration.

- Outstanding filings are reports or updates the company failed to file before dissolution. Form 28 may require you to acknowledge these. Even under a limited restoration, you may need to file certain updates that relate to your purpose, such as a change of directors to sign a transfer. The registrar may also require payment of some past-due fees.

- Court order is a judge’s direction that permits or shapes the restoration. Depending on the circumstances, you may need a court order that authorizes a limited restoration and sets terms. If a court order applies, Form 28 must match it exactly. Any mismatch can void the filing or delay approval.

- Affidavit or supporting evidence is a sworn statement or documents that prove facts in your application. With Form 28, you may attach evidence such as proof of dissolution date, property records, consents, or a draft transaction. You use these to show the registrar the restoration is necessary and defined.

- Notice of articles and company information are the official details recorded for the company, including name, share structure, and directors. A limited restoration can temporarily update some of this information to complete your stated purpose. On Form 28, you confirm what will stay the same, what will change, and for how long those changes must exist to complete your tasks.

FAQs

Do you need a court order to file Form 28?

It depends on your situation. If the company has been dissolved for a long time, or you need the restoration for a specific legal dispute or property issue, you may need a court order authorizing the limited restoration. If a court order applies, match the form to the exact terms and dates in that order. If no order is required, you still must clearly state your narrow purpose and time frame.

Do you have to clear all past filings and fees before a limited restoration?

Not always. Limited restoration is focused on specific tasks. You may still need to pay certain fees or file select updates that directly support the purpose, such as appointing a director to sign a transfer. If your purpose does not require reinstating the full corporate record, the registrar may allow limited changes only for the stated activities. If you want to operate normally again, you should consider a full restoration, which typically requires bringing filings and fees up to date.

Can you request a limited restoration if the company name is no longer available?

Yes. A limited restoration usually allows you to proceed without reclaiming the former name for general use. You use the corporate number and the restored legal status to complete the defined tasks. If your goal includes public-facing activities under the old name, limited restoration may not be enough. You may need a full restoration or a name change.

How long can a limited restoration last?

Only as long as necessary to complete the stated purpose. You choose the period on Form 28. Some purposes take days or weeks; others need more time. If a court order sets the period, you must adopt those exact dates. Ask for a practical cushion, but avoid open-ended timelines. If you underestimate the time, you can apply to extend before the expiry, if permitted.

Can you extend a limited restoration?

Often, yes, but only before it expires. You file a further application that explains why you need more time and confirms the purpose has not changed. If a court order governs the restoration, you may need an updated order. Plan your tasks early to avoid last-minute extensions.

Do you need to be a director or shareholder to apply?

Not always. Creditors, former officers, property holders, or other interested parties may apply if they have a legitimate reason tied to the company. Form 28 asks for your relationship to the company and why restoration is necessary. If you act as an agent, include proof of authority, such as a signed authorization or resolution.

Will a limited restoration let you resume normal business operations?

No. It only allows actions tied to the stated purpose. You should not issue new shares, take on general contracts, or carry on business unless those steps are directly required to complete the stated tasks. If you need to operate, hire, or transact generally, consider a full restoration.

Do you have to notify anyone after filing?

Yes. You should notify anyone directly affected by the restoration, such as banks, land title offices, counterparties, and any court where a claim is active. If a court order requires notice to specific parties, follow it exactly. Keep proof of delivery. This reduces disputes about authority during the restoration period.

Checklist: Before, During, and After the Form 28 – Limited Restoration Application

Before signing

- Confirm the company’s exact legal name and corporate number at the time of dissolution.

- Note the dissolution date and reason for dissolution.

- Define the specific purpose for restoration. Write one or two sentences that are narrow and clear.

- Decide the restoration start and end dates. Build in a realistic buffer.

- Identify the person or entity applying and their relationship to the company.

- Gather proof of authority: signed authorization, resolution, or appointment if you are not a former director or officer.

- Identify any property, contracts, or court files involved. Collect documents like titles, agreements, or file numbers.

- Check name availability only if your purpose requires public use of the company name.

- Collect any necessary consents or letters from affected parties, if applicable to your purpose.

- Determine if a court order is required based on time since dissolution or the nature of your purpose. If yes, obtain the order and review its terms.

- Prepare updated registered office and records office addresses within the province for the limited period.

- Identify who will act as director or authorized signatory during the limited period. Prepare their consent to act if required.

- List any filings that must be updated to carry out the purpose (for example, appoint a director to sign a transfer).

- Set aside funds for filing fees and any outstanding amounts tied to your limited activities.

- Create a short plan and timeline to complete the tasks within the requested period.

During signing

- Verify the company’s legal name, number, and dissolution date. Check for typos.

- Ensure the purpose statement is specific. Avoid general business language.

- Confirm the restoration start and end dates. Align with any court order.

- Insert accurate registered and records office addresses. Use a deliverable physical address.

- Name the applicant and capacity (for example, creditor, former officer, agent). Attach proof of authority.

- Identify any temporary director or signing officer and confirm their details.

- Cross-check all attached documents. Include the court order if required.

- Review fee calculations. Confirm payment method complies with filing instructions.

- Read all certifications on the form. Sign in the correct capacity and date the form.

- Keep a complete copy of the executed form and all attachments.

After signing

- File the Form 28 with the registrar in the manner required. Include all attachments and fees.

- If a court order governs the restoration, attach a filed copy and any schedules cited in the order.

- Track submission and obtain confirmation of filing or restoration status.

- Notify stakeholders immediately upon acceptance: banks, counterparties, land title or personal property office, and any court involved.

- Appoint temporary directors or officers if needed to execute the purpose. File any required supporting updates tied to the limited actions.

- Calendar the restoration expiry date and any interim filing deadlines. Share the dates with your team.

- Complete the permitted transactions promptly. Obtain receipts, registrations, discharges, or transfers as proof.

- If you need more time, apply to extend before the expiry date. Prepare evidence of progress and ongoing need.

- After the tasks are complete, confirm the company’s status will lapse on the expiry date. No further actions are authorized beyond that date.

- Store all records for at least the period required for your transactions, including the application, approval, notices, and proof of completion.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Don’t use a vague purpose statement. If you write “resume business operations,” the registrar may refuse the application or limit it so narrowly you cannot complete your tasks. Be specific, such as “transfer title to [property]” or “settle claim in file no. [number].”

- Don’t request an open-ended timeline. A long or indefinite period raises red flags and can lead to rejection or demands for more evidence. Pick a practical end date and justify it with your plan.

- Don’t forget to match a court order. If a judge set dates, parties, or conditions, your Form 28 must mirror them. A mismatch can void your filing, waste fees, and force you to reapply.

- Don’t overlook authority to sign. If the company has no active directors, you cannot assume signing power. Provide a temporary appointment, a resolution, or an authorization consistent with the limited purpose. Missing authority causes refusal and delays.

- Don’t ignore required notices after approval. Counterparties, registries, and courts need timely notice of the restoration to recognize your actions. Skipping notice risks invalid transactions, rejected registrations, or missed deadlines.

What to Do After Filling Out the Form

- File the application as instructed by the registrar. Include the signed Form 28, all attachments, any court order, and payment. Keep a timestamped copy of everything you submit.

- Monitor the status. If the registrar requests corrections, respond quickly and precisely. Fix typos, clarify your purpose, or attach missing documents without changing the scope unless you refile.

- Once approved, confirm the effective date and the expiry date. Put both dates on your calendar with reminders. Share them with anyone who must act during the restoration.

- Carry out the permitted activities. Examples include completing a property transfer, signing a release, assigning a contract, or taking a defined step in a lawsuit. Tie every action to your purpose. Avoid unrelated transactions to prevent challenges.

- File any related updates necessary to execute your purpose. This may include appointing a temporary director, recording an address change for service, or filing a notice needed to register a transfer. Keep these limited to what the purpose requires.

- Notify all affected parties. Send copies of the approval and your authority to banks, land registries, government agencies involved in the transaction, and any court or counterparty. Ask them to confirm acceptance before you commit to final steps.

- Document every step. Keep copies of executed agreements, registrations, releases, land title search results, and proof of service. Save email confirmations and receipts.

- If you run into timing issues, seek an extension before the expiry date. Explain what you have completed, what remains, and why more time is needed. If a court order governs your restoration, obtain an updated order if required.

- Close out the restoration. When you finish the tasks, verify that all registrations are final and funds have cleared. Confirm that the company will lapse again on the expiry date. If you later discover more actions are needed, apply for a new limited restoration or a full restoration, depending on your goals.

- Store your records securely. Keep the application, approval notice, any court orders, notices sent, and evidence of completed transactions for your required retention period. These records protect you if questions arise later.

- If the registrar rejects the application, review the reason in detail. Correct errors, provide clearer purpose language, or add supporting evidence. If your goals exceed a limited restoration, consider whether a full restoration is necessary and adjust your approach accordingly.

- Finally, update internal stakeholders and advisers. Let them know the restoration window, the permitted actions, and the plan to complete everything on time. Assign clear owners for each task, and hold short check-ins until the work is done.

Disclaimer: This guide is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as legal advice. You should consult a legal professional.