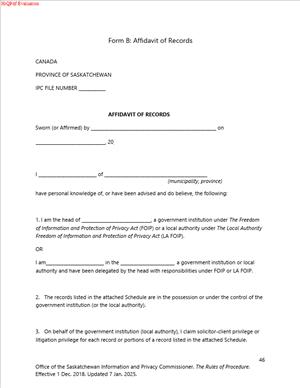

Form B – Affidavit of Records

Fill out nowJurisdiction: Country: Canada | Province/State: Saskatchewan

What is a Form B – Affidavit of Records?

Form B – Affidavit of Records is a sworn statement you use in civil litigation in Saskatchewan to disclose the documents and data that relate to the issues in your case. It is the backbone of document disclosure. You identify what you have, what you had but no longer have, and what you are withholding because of legal privilege. You swear or affirm the affidavit before a commissioner for oaths or a notary public.

Think of “records” in a wide sense. Records include paper and electronic documents, emails, texts, photos, spreadsheets, databases, audio files, videos, social media content, logs, metadata, calendars, and notes. If it can store information, it is a record. The duty covers records you possess, control, or have the legal right or practical ability to obtain.

Who typically uses this form?

Any party in a civil lawsuit in the Saskatchewan Court of King’s Bench. Plaintiffs, defendants, third parties, and anyone added by counterclaim or crossclaim. Individuals, companies, municipalities, and other entities all use it. If you are a corporate party, a knowledgeable officer or employee signs on the corporation’s behalf.

Why would you need this form?

Because the court’s civil rules require full and timely disclosure of relevant and material records. Before questioning (examination for discovery), each party must disclose records through a sworn affidavit. This gives everyone a clear map of the evidence that exists, where it is, and what is being withheld under privilege. It reduces surprise and narrows the issues.

Typical usage scenarios

- A motor vehicle accident lawsuit. You disclose photos, repair invoices, medical records, insurance communications, and related emails or texts.

- A construction dispute. You disclose contracts, change orders, site diaries, RFIs, pay applications, emails, schedules, meeting minutes, and as-built drawings.

- A commercial debt claim. You disclose the credit agreement, guarantees, invoices, statements of account, collection notes, and payment records.

- An employment claim. You disclose the employment agreement, policies, performance reviews, emails, payroll records, and termination documents.

- A professional negligence claim. You disclose engagement letters, working papers, reports, emails, and relevant file notes.

The affidavit organizes your disclosure into schedules:

- Schedule A: Relevant and material records in your possession or control that you will produce.

- Schedule B: Relevant and material records you no longer have, with details of what happened to them and where they might be found.

- Schedule C: Relevant and material records you claim are privileged and will not produce, with enough description to identify them without revealing the privileged content.

You then produce the Schedule A records to the other parties, usually with an index or Bates numbering. You do not attach the records to the affidavit unless a court order directs otherwise. You serve the sworn affidavit on the other parties and keep it updated as new records are found.

When Would You Use a Form B – Affidavit of Records?

You use Form B early in the discovery phase, after pleadings close and before questioning. In many cases, the court rules or a scheduling order sets the timeline. If another party requests your affidavit, you must respond within the set time. If you delay, the court can order you to serve it by a deadline and may award costs against you.

Practical examples:

- You are a plaintiff suing for unpaid invoices. You serve your affidavit listing the contract, invoices, delivery confirmations, and your email chains with the customer. You include bank statements showing partial payments. You list your lawyer’s settlement notes as privileged in Schedule C.

- You are a defendant in a personal injury claim. You serve your affidavit listing your photos of the accident scene, repair estimates, and your text messages from the day of the incident. You include an explanation for a dashcam card that was overwritten in Schedule B.

- You are a contractor defending a claim about delays. You disclose baseline and updated schedules, daily logs, weather records, correspondence with the owner and subcontractors, and change order files. You also list consultant reports you received. You claim privilege over emails with your lawyer after the dispute arose.

- You are a municipality in a zoning dispute. You disclose council minutes, staff reports, zoning bylaws, policy documents, GIS maps, and citizen correspondence relevant to the decision at issue.

Typical users include self-represented litigants, business owners, landlords, tenants, insurers, project managers, HR managers, and corporate officers. If you manage records for a company, you coordinate with IT to identify custodians and data sources. If you are an insurer controlling the defence, you help the insured collect and disclose records while safeguarding privilege.

Beyond the standard discovery timeline, you may need a Form B when responding to a court application that raises factual issues tied to documents. You may also update your affidavit if you discover new records, receive a third party’s production, or correct an earlier omission.

Legal Characteristics of the Form B – Affidavit of Records

Form B is a sworn affidavit. That makes it legally binding. You confirm under oath or affirmation that you have made a diligent search and that your disclosure is complete to the best of your knowledge. False or misleading affidavits can lead to serious consequences, including adverse cost awards, evidentiary sanctions, contempt, or perjury charges in extreme cases.

What ensures enforceability?

The rules of court require full disclosure of relevant and material records. Judges can make production orders, set timelines, require answers for deficiencies, and strike pleadings in severe cases of non-compliance. The court can draw adverse inferences if records were destroyed or withheld without valid reasons. Costs often follow disclosure motions, which encourages cooperation.

Privilege protects certain records even though they are relevant. The most common heads of privilege are:

- Solicitor-client privilege: communications with your lawyer for legal advice.

- Litigation privilege: documents created for the dominant purpose of litigation.

- Without prejudice settlement privilege: genuine settlement communications.

Privilege survives disclosure obligations, but you must list privileged records in Schedule C with enough detail to substantiate the claim without disclosing the privileged content. Over-claiming privilege can draw challenges; under-claiming can waive it. Redactions are common for privileged parts of otherwise producible documents. You state the basis for each redaction.

Document relevance and materiality are tied to the pleadings. If an issue is raised in the statement of claim, defence, or counterclaim, related records are generally relevant. Materiality asks whether the record could influence the outcome of an issue in the case. When in doubt, err on the side of listing the record. You can reserve your position and ask the parties to agree on reasonable limits.

Electronic records need special care. The duty to preserve starts when litigation is contemplated, not only after it is filed. You should issue a litigation hold to custodians, suspend routine deletion, and preserve sources like email accounts, shared drives, cloud storage, mobile devices, messaging apps, collaboration tools, and backups where feasible. Altering or deleting relevant records after this duty arises can lead to spoliation findings and sanctions.

Confidentiality is not a bar to disclosure. If records contain sensitive business or personal information, you can seek a confidentiality agreement or a protective order. You still list the record and, unless privileged, you produce it with appropriate safeguards (redactions for non-relevant personal data, access restrictions, or “counsel’s eyes only” in rare cases).

Your duty to disclose is ongoing. If you discover new records or your possession or control changes, you must supplement your affidavit and produce the new records promptly. This continuing obligation remains through trial.

Finally, you usually serve your affidavit on all parties but do not file it with the court unless a judge directs you to or you need it for a motion. Keep a clean copy signed by the deponent and the commissioner for oaths, and maintain a production set with Bates numbers.

How to Fill Out a Form B – Affidavit of Records

Follow these steps to complete the Saskatchewan Form B – Affidavit of Records. Adjust for your case specifics and any court directions.

1) Prepare before you draft

- Identify issues: Read the claim, defence, and any counterclaims. Make a list of issues. Your disclosure should match these.

- Preserve records: Issue a litigation hold. Stop automatic deletions. Alert IT and custodians about email, chats, texts, and shared folders.

- Map data sources: List paper files, email accounts, cloud drives (e.g., OneDrive, Google Drive), local drives, phones, messaging apps, financial systems, project management tools, and backups.

- Identify custodians: Who likely has relevant records? Include employees, former employees, consultants, and contractors.

- Collect and review: Gather records in a controlled way. Keep originals. Work from copies for review. Use a simple index or eDiscovery tool if the volume is high.

- Screen for relevance and privilege: Separate what relates to the issues. Flag privileged content. Plan redactions where needed.

2) Complete the caption

- Court heading: Use the Court of King’s Bench for Saskatchewan. Include the Judicial Centre (e.g., Regina, Saskatoon, Prince Albert).

- Court file number: Insert the correct file number.

- Style of cause: List the parties exactly as on the pleadings, with roles (Plaintiff, Defendant, etc.).

- Title of document: “Form B – Affidavit of Records.”

3) Identify the deponent

- Name and role: State your full legal name and your role in the case. If you are a corporate representative, state your position and authority to swear for the corporation.

- Contact details: Insert your address and contact information as the form requires.

- Capacity statement: Confirm you are knowledgeable about the records and have made a diligent search.

Example wording: “I, Jordan Smith, of the City of Saskatoon, in the Province of Saskatchewan, am the Operations Manager of ABC Construction Ltd., the Defendant in this action, and as such have knowledge of the matters hereinafter deposed to.”

4) Describe the search

- Scope: Briefly describe where you searched and which custodians you contacted.

- Methods: Note key systems and date ranges (e.g., “searched emails from January 2022 to present”).

- Preservation: Confirm you preserved relevant records once litigation was anticipated.

Example: “I conducted a diligent search of paper project files, the company email accounts of the Project Manager and Site Superintendent, the Procore project folder, and the accounting system for invoices and pay applications from March 2021 to September 2022.”

5) Organize schedules

Create three schedules. Use consistent numbering and clear descriptions. Each entry should allow a reader to identify the record without reviewing it.

- Schedule A: Records in your possession or control that you will produce.

- Number each item. Include date, author/recipient (if applicable), type of record, a short description, and location or file path if helpful.

- For electronic records, indicate format (e.g., native Excel, PDF, JPEG) and whether metadata is preserved.

- Group similar items by category if numerous (e.g., “Emails between A and B dated May 1–June 30, 2023, regarding Change Order 4”).

- Schedule B: Relevant records you no longer possess or control.

- Describe each record or category, when you last had it, why it is no longer available, and who likely has it now.

- If destroyed or overwritten, explain how and when. If a third party holds it, name the custodian if known.

- Schedule C: Privileged records.

- Claim privilege record-by-record or by well-defined category.

- For each entry, give date, author/recipient (if applicable), general subject, and type of privilege (e.g., solicitor-client, litigation privilege).

- Do not reveal the content. Provide enough information to assess the claim.

Examples of entries

- Schedule A

1. March 12, 2022 – Signed Construction Contract between ABC Construction Ltd. and XYZ Developments Inc. (PDF).

2. Apr 5–Jul 30, 2022 – Emails between J. Smith (ABC) and L. Chan (XYZ) re: project delays and extensions (PST export; produced with metadata).

3. June 15, 2022 – Pay Application No. 4 with backup (PDF).

4. May 2022 – Site photos (25 JPEG images) showing foundation work.

- Schedule B

1. Daily Site Diary for April 10, 2022 – maintained by former Site Superintendent; last seen July 2022; likely in possession of former employee. ABC does not have a copy.

2. Dashcam video from April 9, 2022 – file auto-overwritten on device on April 30, 2022, before litigation hold. No longer available.

- Schedule C

1. Sept 1, 2022 – Email from J. Smith (ABC) to counsel re: legal advice on claim strategy (solicitor-client privilege).

2. Sept–Oct 2022 – Draft claim summaries prepared at counsel’s request (litigation privilege).

6) Address redactions and confidentiality

- If you must redact personal identifiers or non-relevant confidential business data, state that you are producing a redacted version and identify the basis for redaction.

- If the record is sensitive, consider proposing a confidentiality agreement or protective order. Note such measures in a covering letter, not in the affidavit body.

7) Deal with third-party and external records

- If a bank, medical provider, or other third party holds relevant records, list them in Schedule B if you do not have them.

- Offer reasonable cooperation, such as providing consents or requesting the records.

- If you have a legal right to obtain the records on demand (e.g., your own bank statements), treat them as within your control and obtain them for production.

8) Complete the deponent’s statements

The form will include standard statements. Ensure you:

- Swear you have made a diligent search.

- Confirm the schedules are complete to the best of your knowledge.

- Undertake to produce Schedule A records for inspection and copying.

9) Swear or affirm the affidavit

- Arrange for a commissioner for oaths or a notary public in Saskatchewan.

- Sign in their presence. They complete the jurat, stating when and where you swore or affirmed, and their name and authority.

- If you need to correct something after swearing, you generally swear a fresh affidavit rather than altering the signed document.

10) Prepare the production set

- Produce Schedule A records as agreed (electronic production is standard).

- Use a consistent file naming convention and Bates numbering. Example: ABC_000001.pdf.

- Include an index matching Bates numbers to Schedule A entries.

- For electronic spreadsheets and databases, produce native files unless the parties agree otherwise. Note any password protection and provide access details securely.

11) Serve and keep proof

- Serve the sworn affidavit and production set on all parties of record.

- Keep proof of service. Retain your original signed affidavit and a copy of everything you produced.

12) Update as needed

- If you discover new relevant records, supplement your affidavit promptly. Use the same structure, and identify what is new.

- If privilege status changes (e.g., you decide to waive privilege over a record), serve an updated Schedule C and produce the record.

Practical tips to avoid common mistakes

- Do not attach Schedule A records to the affidavit unless the court orders it. Produce them separately.

- Be specific but concise in descriptions. “Email re: payment terms” is better than “Email.”

- Avoid blanket privilege claims. Log each privileged item or a narrow, well-defined set.

- Do not omit negative facts. Disclosure is not advocacy. If a record exists and is relevant, list it.

- Preserve metadata when it matters (e.g., email headers, file creation dates). Agree with other parties on a simple production protocol.

- If a record is not in English or French, note the language and consider providing a translation for use at discovery or trial.

- Coordinate within your organization. No single person knows every record source. Check with IT, finance, and operations.

What to do if the other side’s affidavit is deficient

- Ask for particulars. Identify missing categories or obvious gaps (e.g., no emails disclosed in an email-heavy dispute).

- Request a supplemental affidavit and production.

- If there is no cooperation, bring a motion for a better affidavit of records and production, with costs.

Final check before you swear

- Does the caption match the most recent style of cause?

- Have you described your search?

- Are all three schedules present, properly labeled, and complete?

- Are privilege claims clear and defensible?

- Is your production set ready and consistent with Schedule A?

- Are you prepared to answer questions at discovery about your search and the records listed?

If you follow these steps, your Form B – Affidavit of Records will meet your disclosure obligations in Saskatchewan. You will be ready for questioning and set up to avoid unnecessary disclosure disputes.

Legal Terms You Might Encounter

- Affidavit means a sworn statement of facts. In this form, you swear that your record list is complete and accurate to the best of your knowledge. You sign under oath in front of an authorized person.

- Deponent is the person who swears or affirms the affidavit. If you are a party, you likely act as the deponent. If you are a company, you choose a knowledgeable representative to act as the deponent.

- Commissioner for Oaths or a Notary Public is the official who administers your oath or affirmation. They verify your identity and witness your signature on Form B.

- Records are any documents, data, or materials relevant to the lawsuit. This includes emails, texts, spreadsheets, PDFs, photos, videos, databases, call logs, notes, contracts, and physical files. It also includes drafts and metadata where relevant.

- Possession, Control, or Power describes how you relate to a record. Possession means you physically hold it. Control means you can get it on demand, even if someone else holds it. Power means you have a right to obtain it. In Form B, you must list records across all three categories.

- Relevant and Material means a record can help prove or disprove a fact in the case. The threshold is low. If it might matter to an issue, include it. When unsure, list it.

- Privilege is a legal right to withhold certain records. Common types include solicitor‑client, litigation, settlement, and without prejudice communications. You must list privileged records in the protected section without revealing the privileged content.

- Redaction means removing or blacking out sensitive content within a document. Use it to protect privileged parts or personal information. You still list the record and explain why parts are withheld.

- Schedules are the sections within Form B where you group records. One schedule lists the records you will produce. Another lists records you claim are privileged. A third lists records that are relevant but no longer in your possession or control. The form prompts you to place each record in the right schedule.

- Jurat is the block at the end of your affidavit where the commissioner or notary signs. It records the place, date, and that you swore or affirmed the contents. Check that the jurat matches your details.

- Service means delivering the affidavit to the other party in the lawsuit. Follow the accepted methods. Keep proof of how and when you served it.

- Production refers to providing copies of non‑privileged listed records to the other side. Production can be rolling. You may send more documents after the initial list.

- Supplementation means updating your affidavit if you find new records or if circumstances change. You cannot sit on new information. File or serve an updated list as required.

FAQs

Do you have to list records that hurt your case?

Yes. You must list all relevant and material records. This includes records that support or undermine your position. Withholding unhelpful records can cause serious penalties.

Do you need to include emails and texts from personal devices?

Yes, if they are relevant and within your possession, control, or power. Work with your IT or vendor to collect them properly. Preserve metadata where possible.

Do you include records that you no longer have?

Yes. You list them in the schedule for records no longer in your possession or control. Explain what the record is, who has it, and why you no longer have it. Include details that help the other side locate it.

Do you need to attach the documents to the affidavit?

No. Form B lists and describes the records. You then produce non‑privileged records separately. Attachments are not usually required unless the form or court directs it.

Do you claim privilege by leaving a document off the list?

No. You must list privileged records in the privilege schedule. Give enough detail to identify the document without revealing privileged content. State the privilege claimed and the basis.

Do you have to search backups or archives?

You must make a reasonable, good‑faith search. Consider backups and archives where relevant and accessible. If restoring backups is not reasonable, document why and explain it in your notes.

Do you need a specific person to sign for a company?

Yes. Choose a person who knows the records and the issues. They should understand the systems, custodians, and collection steps. They will swear the affidavit as the company’s representative.

Do you have to update the affidavit if new records appear?

Yes. You must supplement when you find new relevant records or when privileges change. Send an updated list and produce new non‑privileged records promptly.

Checklist: Before, During, and After the Form B – Affidavit of Records

Before signing: Information and documents you need

Case overview:

- Your pleadings and the other side’s pleadings.

- Key issues, dates, and claims to guide your search.

Custodian list:

- Names and roles of people likely to hold records.

- Departed employees and shared mailboxes.

Systems map:

- Email, chat, document management, cloud storage, phones, and drives.

- Accounting, CRM, HR, and project tools.

- Physical locations: file rooms, off‑site storage, personal notebooks.

Search plan:

- Date ranges, keywords, and topics.

- Locations to search and any excluded sources.

- Steps to preserve, collect, and de‑duplicate.

Record inventory:

- Contracts, letters, and memos.

- Meeting notes and notebooks.

- Emails, texts, and chats.

- Invoices, receipts, and statements.

- Photos, videos, and call logs.

- Spreadsheets, reports, and databases.

Privilege assessment:

- Communications with your lawyer.

- Notes prepared for the lawsuit.

- Settlement offers and without prejudice emails.

- Documents that mix legal and business advice.

Third‑party records:

- Documents held by affiliates, consultants, or vendors.

- Client files and regulatory submissions.

- Insurer correspondence and adjuster notes.

- Lost or unavailable records:

- What was lost, when, and why

- Who might have it now, and how to request it.

Identity details:

- Exact legal names of parties.

- Court file number and location.

- Your full name, title, and contact details.

Execution logistics:

- Time with a commissioner or notary.

- Photo ID and any remote commissioning requirements.

- Quiet room and complete, final version of the form.

During signing: Sections to verify

Caption and file number:

- Party names, court location, and file number match your pleadings.

Deponent information:

- Your name, role, and authority (individual or corporate).

- If corporate, your title and basis for knowledge.

Completeness statement:

- The oath states that you made a diligent search.

- It covers records in your possession, control, or power.

Schedules:

- Non‑privileged, producible records are clearly listed.

- Privileged records are separate with proper descriptions and grounds.

- Records no longer held are listed with details and the current holder, if known.

- Descriptions:

- Clear titles, dates, authors, recipients, and short subject lines.

- Avoid vague labels like “miscellaneous emails.”

Numbering:

- Record IDs are sequential and consistent across schedules and productions.

- Page counts or file counts are noted where useful.

Redactions:

- Redaction reasons are noted if parts are withheld.

- Clean and redacted copies are stored correctly.

Jurat:

- Correct city or town, date, and commissioner or notary details.

- Your signature matches your printed name.

Exhibits (if any):

- Each exhibit is labeled and referenced properly.

- Exhibit pages are legible and complete.

Formatting:

- No blanks or stray draft marks.

- Dates use a consistent format.

- All cross‑references match.

After signing: Filing, notifying, and storing instructions

Serving:

- Serve the affidavit and schedules on the other party.

- Use an accepted delivery method and keep proof of service.

- Note any deadlines in your calendar.

Producing non‑privileged records:

- Produce the documents listed in the non‑privileged schedule.

- Match file names to your record IDs.

- Use a standard format (PDF, native files, or both) as appropriate.

Privilege log:

- Provide the privilege schedule as your privilege log.

- Include date, authors, recipients, subject line, and privilege type.

- Keep a private memo supporting each privilege claim.

Follow‑up:

- Track any requests for better descriptions or missing items.

- Respond with clarified entries or additional productions.

- Document each step on a production log.

Supplementation:

- Set a recurring reminder to reassess for new records.

- Issue an updated affidavit if new items appear.

Storage:

- Save a signed PDF and the working files.

- Keep native documents in a secure, organized structure.

- Maintain chain‑of‑custody notes for collected data.

Confidentiality:

- Apply protective markings if required.

- Use secure transfer tools for sensitive files.

Internal alignment:

- Brief your team on what was produced and withheld.

- Align on messaging for meet‑and‑confer discussions.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- Don’t forget to search all locations, including personal devices.

Consequence: You risk incomplete disclosure, sanctions, and credibility damage. Courts expect a reasonable, documented search across all likely sources.

- Don’t mix privileged and non‑privileged items in one schedule.

Consequence: You can waive privilege or trigger disputes. Keep privileged items in the privilege schedule with clear descriptions and grounds.

- Don’t use vague descriptions like “various emails.”

Consequence: The other side may challenge your list and seek more detail. Use dates, authors, recipients, and short subjects that identify the document.

- Don’t ignore records you no longer hold.

Consequence: You appear evasive and may face orders to explain. List them with as much detail as you have and indicate who likely holds them now.

- Don’t let an unprepared person sign.

Consequence: The affidavit can be discredited. Choose a deponent who knows the records and the search process and can explain them if required.

What to Do After Filling Out the Form

- Confirm whether you must file the affidavit with the court or only serve it. Practices differ. If filing is required, prepare a signed PDF, follow the accepted filing method, and note any fees. Keep filing confirmations.

- Serve the affidavit on every party entitled to it. Use a delivery method that meets the rules. Capture proof of service. Note any production deadlines tied to service.

- Produce non‑privileged documents listed in your main schedule. Match each document to its record ID so the other side can track it. If a document exists in multiple formats, choose the most useful one. Preserve metadata for electronic files when relevance requires it.

- Deliver the privilege schedule as your privilege log. Use consistent descriptions. Identify the privilege type and a brief basis. Do not reveal privileged content. Keep a private index with fuller notes in case of challenge.

- Address gaps or objections quickly. If the other side asks for better descriptions or additional records, meet and discuss the scope. You can revise descriptions, produce more items, or explain why requests are not reasonable. Document your position in writing.

- Plan rolling productions if volume is high. Set a cadence, such as weekly tranches. Update your index after each tranche. Make sure numbering stays consistent and unique.

- Supplement when new records surface. New custodians may emerge. Systems might reveal archived data. Issue an updated affidavit and produce the new non‑privileged documents. Flag what changed and why.

- Protect sensitive information. If records include personal or confidential data, consider redactions. Use protective markings where appropriate. If disputes arise about sensitivity, seek agreement on handling or raise it with the court as needed.

- Track downstream use. Records listed in Form B may be used in questioning or at trial. Keep clean copies ready. Maintain a witness set, an exhibit set, and a working set. Align your team on which version is authoritative.

- Close the loop with your client or business team. Explain what was listed, what was produced, and what was withheld. Confirm that legal holds remain in place until the case ends. When the matter closes, follow any required steps for returning or destroying records.

- Keep a clear audit trail. Retain the signed affidavit, proof of service, production logs, correspondence, and any supplemental filings. These materials help you show a diligent process if questions arise later.

- If you discover a material error, fix it quickly. Prepare an amending or supplemental affidavit. Serve it and, if required, file it. Explain what changed and replace any affected productions.

- If the other side challenges your privilege claims, follow a measured process. Review the challenged entries. Strengthen descriptions where possible. Consider limited redactions instead of withholding the whole document. If needed, ask for a method to resolve the dispute without exposing privileged content.

- Finally, keep momentum. The affidavit is a snapshot. Discovery continues. New facts and records will emerge. Keep your inventory current so you can respond quickly to requests and prepare for questioning.

Disclaimer: This guide is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as legal advice. You should consult a legal professional.